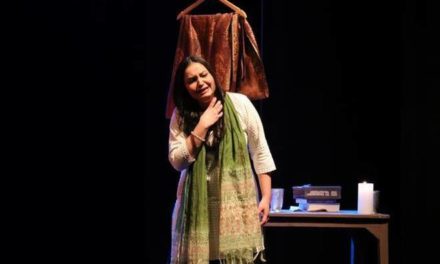

Amy Liptrot’s bestselling memoir, The Outrun (2016) has recently been genre hopping. In January 2024, the film version, by German director Nora Fingscheidt, premiered at Utah’s Sundance Festival and is soon to be released in the UK, while in early August the memoir was turned into a stage play for this year’s Edinburgh International Festival. Adapted by well-known Scottish stage and screen writer, Stef Smith, and directed by Vicky Featherstone, former Artistic Director of London’s Royal Court, the production boasts a strong cast and creative team. It’s the story of a young woman (named Woman, played by Isis Hainworth) from Orkney, her fall into alcoholism, her move to Edinburgh and then London, her near destruction, rehabilitation and finally her return to the tiny Orcadian island of Papa Westray. Avoiding the risk of retelling the story in an over-chronological fashion, Stef Smith presents the various stages in the narrative in a sequence of short scenes, some of them as flashbacks set in different times and spaces, charting the woman’s psychological turmoil. Onstage action is contextualised by Lewis den Hertog’s splendid video images, conjuring up the beautiful, rugged Orcadian landscape in sharp contrast to the dystopian inner cityscape, together with mesmerising lighting (designer, Liz Powell) and sound (Kev Murray) effects. A five-strong Chorus (directed by Michael Henry) occasionally heightens the realism, by singing or repeating words from Woman’s direct audience addresses. Particularly moving are the early scenes, set in the close-knit community on Orkney, where Woman was born. Her bipolar father (Dad, played by Paul Brennan), struggles to understand his daughter and the feeling is mutual. The girl’s language tellingly conveys a visceral attachment to her island home. It is littered with references to the rural environment (Outrun denotes a huge field in front of the family farm), including the animals, fish, plants and trees there. Little gems of language pop up every now and then, like, “Taking it all in like a basking shark’. At the same time, there are early signs of her addiction; she stealthily slugs a drink or two when no one is watching. More predictable are the Edinburgh and London scenes, when she takes on a new identity. As she puts it, “she wants to experience everything” and so dresses to the nines, goes clubbing and allows drink to take over her life. Boy (Seamus Dillane), who becomes her partner, remains a sketchy figure, albeit significant in Woman’s life. For the first time she finds a man who loves her, but her addiction means he hasn’t the courage to stay with her. In a pivotal scene, he throws her out, refusing to have anything more to do with her. Undoubtedly, the lack of depth of Boy’s character and others depends on the source memoir, where Any Liptrot sets out to dig as deep as possible into her own identity and addiction. On the point of self-destruction, when she feels like ‘a vanishing lady,’ her words, Woman decides to join a therapy group, in a scene where she must finally confront her demons. In the final scenes, having broken the addiction, Woman returns to the Orkneys. While the dialogue deftly points to some of those things that can trigger off a potential relapse, like somebody offering Woman a drink, or her remembering the taste and smell of alcohol, the pace grew over-slow and potentially dramatic moments weren’t fully exploited. Towards the end the adapter seemed not to know exactly when to bring the play to its conclusion. Having said that, Woman, masterfully brought to life by Isis Hainworth, drew me in and made me far more aware of the issues of a person suffering from addiction as well as the impact on their friends and family.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Margaret Rose.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.