Think of a film set where the audience gathered on the streets are not fully aware that they are watching a film being made: they know there is action and fireworks are coming but not a lot else. They congregate in the city centre at the corner of where Zenteno Street meets Alonso de Ovalle and wait – many of co-director Alejo Moguillansky’s films gravitate around processes of waiting. Clues appear. A truck with a sound system begins to blast out 1980s disco pop and the audience members who are gathered on the pavements sway and dance to the music. Moguillansky uses a megaphone and microphone to give a series of instructions to the audience. The show’s co-director dancer-choreographer Luciana Acuña — founder-director with the late Luis Biasotto of the innovative dance-theatre company, Grupo Krapp — , hovers close by. A camera is set up and a camera operator, the Chilean cinematographer Manuel Vlastelica, is introduced by Moguillansky. A film is about to be made, we are invited to watch, to always remain behind the camera and follow the instructions. The soundtrack emerges from the speakers on the truck travelling alongside the camera. And then there’s the protagonist, or rather all three of them, that are about to begin their routine. Moguillansky announces the credits: dancers Vinícius Francês, Luciana Acuña and Francisca Espinoza; DJ Richard Bauer; costumes Mariana Tirantte; producer Gabriela Gobb; and the local on the ground Chilean producer Rodrigo Moreno. Credits all completed, it’s time for the camera to roll. The audience may think Efectos especiales (Special Effects) is about to begin. Effectively the performance began when the first audience member arrived at the street corner where the crew are setting up the film set.

Alejo Moguillansky gives instructions to the audience with Luciana Acuña at his side. Photo: Maria Delgado

Dancer Vinícius Francês in red patterned kilt and baggy floating top is running: we don’t know why or where to but he’s clearly being pursued by an unknown assailant (possibly the camera, possibly his own demons); he dances across the parked cars, the walls and doorways. He clings to railings, trying to meld into the landscape; he moves stealthily and loosely — his tall frame bending and stooping, arching and sweeping. At times, his moves recall a silent movie routine, his face contorted with anxiety and his hands and feet reaching out in different directions. It is almost as if he is drunk, swaying unsteadily in the light evening breeze. The spectators run alongside him as he meets a number of obstacles: fireworks explode around him, rain (from a giant hose) saturates him and gunfire runs him down – he collapses to the ground as snow falls around him (another generated “special effect”).

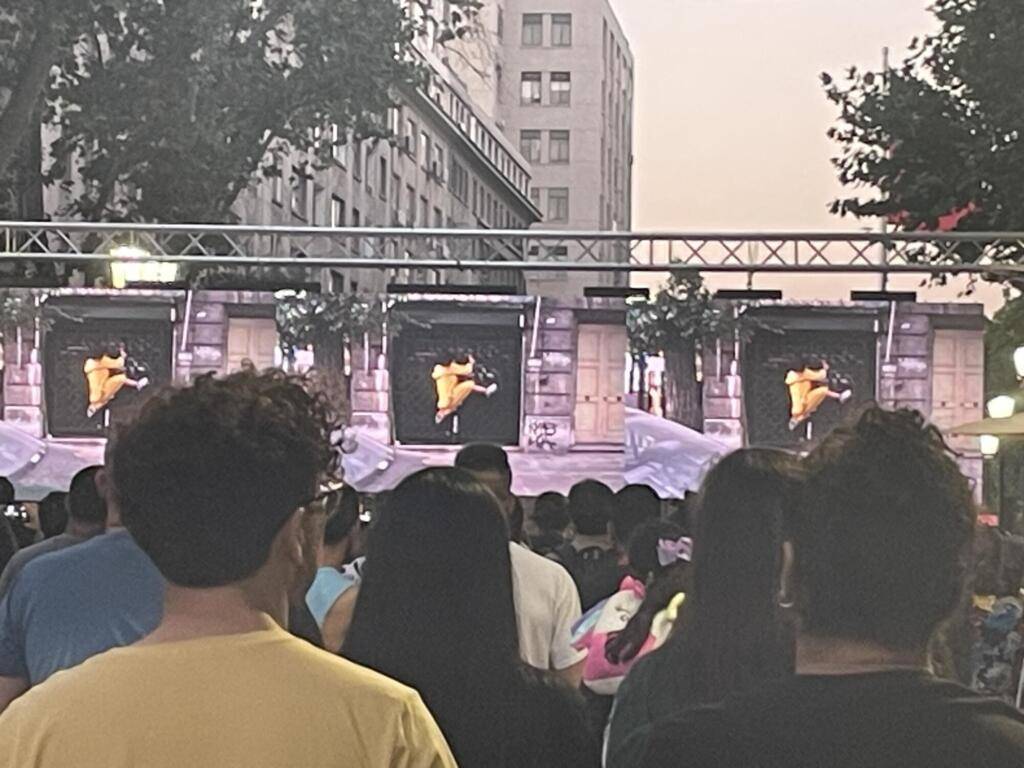

The gathered spectators are then invited to congregate around the corner on Paseo Bulnes as the film shot by Vlastelica and directed by Moguillansky is projected on a large screen. The fiction we have witnessed being made is a quest narrative – a protagonist, a hidden assailant, a death, catharsis. There are moments when spectators spill onto the screen, captured by Vlastelica’s camera despite the clear instructions given by Moguillansky to always remain behind the camera. The spectators can be seen hovering around the borders of the frame: awkwardly trying to get out of the camera’s all-seeing eye. Reality introduces into the best laid plans, rupturing the film with its awkwardness and chaos. Art cannot always be as neat as the director may wish. The audience in this production cannot but be part of the action and the artefact that’s been created.

Take 2 of the film has a different dancer, Luciana Acuña, undertake a similar routine. A more compact figure, she darts and dashes, caressing the walls and cars. Her bundle of dark curls bob around her face as she moves. Her eyes are watchful and fearful. A bundle of energy, she rolls and juts. Hers is a more feverish presence, a more precise choreography. In her bright yellow mac and matching shorts, she cuts a distinctive figure whose attire makes it difficult for her to meld into the 1930s architecture. The pattern of fireworks, smoke, rain, gunshots and snow is the same but the rhythm and body language are different. At the shoot’s end, we all move to the screen on Bulnes to watch take 2.

The audience watching Luciana Acuña on the screen erected on Paseo Bulnes. Photo Maria Delgado

Take 3 introduces a third dancer, Francisca Espinoza: her blonde hair flying around her head, her sequined dress twinkling in the early evening sun. Her dance moves are looser, like a disco dancer transported from the safety of the dance floor into a city where she fails to blend in. This time the spectators are invited to be part of the action – running into the camera and falling down with the protagonist as the gunshots are fired.

Take 3 is projected alongside the other two as a triptych of works. The storyline may be almost the same but what strikes the viewer are the differences between each: what fear looks like for each of the dancers; how each straddle the cars, walls, doorways, streetlamps, bins and bicycles along the way. The audience are openly framed in take 3 – they wave and smile, they “perform” with props and children in hand. They are very much part of the action. Not all are able or willing to follow Moguillansky’s instructions. Part of the piece’s fun lies in watching the different spectators flaunting or disobeying the instructions, some intentionally, some not.

The audience play dead alongside the dancer in the Rio Preto performance of Efectos especiales (Special Effects). Photo: Mateus Jose Maria

The street scene offers a stage for observing, for reframing and repositioning; it allows fictions to be constructed under a policed process. There are producers with walkie talkies shepherding the audience, police stop the traffic to cut the circulation of cars and permit the filming – behind every piece of art lies an invisible army of people ensuring the process is completed. It takes a lot of labour to “make” work that looks “real”. This army is very clearly on show in Special Effects.

The joy of this production lies in adrenaline rush as the audience pursue the dancer, in the fun of seeing the urban streets presented in a different light, in the game that we are invited to be part of, in the pleasure of dancing along to Depeche Mode, The Clash and The Weather Girls through this sleepy Santiago street. Special Effects allows for this street, not far from the Moneda Place, to become, for a short while, a space for congregation. It becomes, as night falls, at once a site of danger and pleasure, where the real and fiction converge. Think François Truffaut’s Nuit américaine/Day for Night (1973) meeting La Fura dels Baus and you might get somewhere near the tone of this gloriously inventive production.

Efectos especiales plays at Santiago a Mil on 18 and 19 January 2024. Daniella Santibáñez Monasterio replaces Francisca Espinoza as the third dancer on the performance of 19 January.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.