Primavera con una esquina rota (Springtime in a broken mirror) has acquired a legendary status. First produced by Teatro Ictus in 1984, this adaptation of Mario Benedetti’s eponymous 1982 novel was restaged in 2023, on the fiftieth anniversary of Pinochet’s coup, in association with Estadio Nacional Memoria Nacional – the football stadium where so many political prisoners were held, tortured and killed in the aftermath of the coup. The play revolves around the history of a family suffering the consequences of exile and imprisonment beginning in 1973 – the year that marked not only the Pinochet coup but that of the Uruguayan dictatorship, where democratically elected President Juan María Bordaberry shut down the Parliament and installed a military junta. The dictatorship lasted until 1985 with Benedetti fleeing into exile – moving from Buenos Aires to Lima, Cuba and then Madrid and Mallorca. He returned to Uruguay in 1985. Springtime in a broken mirror is the only novel he published in exile.

The action takes place concurrently in a Uruguayan prison where, following the coup, Santiago (Daniel Muñoz Bravo) is jailed and Mexico where his family, wife Graciela (Paula Sharim Kovalskys), daughter Beatriz (Camila Oliva Olivos) and father Rafael (Roberto Poblete), are in exile – joined, as the action opens, by his close friend Rolando (Nicolás Zárate Zavala). Rafael is trying to adapt to a new country but struggling, and finds he has nothing positive to write to his son to lift his hopes, so chooses not to write at all. Santiago’s young daughter Beatriz is increasingly isolated from her mother, trying to make sense of the situation the family find themselves in while dealing with the accusations made about her father from schoolmates whose families, whatever their political affiliations, clearly resent the presence of the Uruguayan exiles. Santiago’s wife Graciela seeks comfort in the arms of Rolando – a relationship that puts in jeopardy what had been a close friendship between the three. Santiago is repeatedly shown on stage in curtailed positions where his hands are behind his back or he is cramped into the corner by the stage right wall. Imprisonment is both physical and a state of mind here. His body contorts, his hands grip the side wall of the theatre. It’s an existence where he cannot stand up straight – in contrast with the lithe, playful moves that mark Santiago, Roberto and Graciela’s time before the coup. Unlike Santiago, Graciela, Beatriz, Rolando and Rafael all have freedom, but they are unable to make the most of it.

This is not a restaging of the 1984 production, rather Emilia Noguera provides a new adaptation that also draws on the historical circumstances of the initial run in 1984-85 where actor Roberto Parada learned, during one of the performances in late March 1985, that his son, José Miguel Parada, had been assassinated. After being told of the murder during the interval, he went on stage for the second half and then dedicated the performance to the memory of his son. The theatre filled with Chileans who had learned of the crime and came to show solidarity, handling Parada flowers at the end of the show.

This episode, which is indelibly part of the history of this production, is expertly woven into the new adaptation: a moment when actors Camila Oliva Olivos and Nicolás Zárate Zavala, step out of the roles of Beatriz and Rolando respectively to read from what I presumed was Damián Noguera’s Autobiografía de mi padre (Autobiography of My Father) where the memories of Héctor Noguera, who was in the original cast, are captured in prose by son Damián. The action stops, as this moment is recalled. The actors read from the published book – a mode of capturing the extraordinary parallels between the stories – two fathers, two sons, separation, imprisonment. One story ends in tragedy, the other sees Santiago released from prison but to an uncertain future as Rolando and Graciela have begun a relationship that they have been keeping from him.

Tamara Figueroa’s set is simple but effective: six chairs at the back of the stage where the cast of six sit and watch the action when they are not “performing” in role. Three chairs at the front are moved round to create different configurations: the three friends discussing dialectics in a spirited manner; a day out at the beach; Rafael’s home where friend Lila (María Elena Duvauchelle Concha) serves as an outsider – an audience surrogate that the characters can confide in; the tense home shared by Graciela and Beatriz where communication isn’t easy. Past and present intersect, commenting on each other in informed ways. They are inseparable: the pre-coup days enjoyed by the group haunt both Santiago’s prison days and the family’s Mexican existence. Phone conversations between Rolando and Graciela are expertly staged with each actor at an opposite side of the stage: it is as if the characters fear coming too close. Whereas Santiago is measured and philosophical, with secrets that haunt him, Rolando is quick tempered and emotive. Their relationship is beautifully captured by Daniel Muñoz Bravo and Nicolás Zárate Zavala — their joyful singing with Rolando on the ukulele is gorgeous. The audience experience the buoyant Rolando arriving at Rafael’s Mexican home to bring a letter from Santiago smuggled from prison; Rolando is drunk and unsteady on his feet, awkward and obtrusive. Lila observes and offers coffee: Rafael wants him sober. It’s a wonderful scene where no-one knows quite what to do and Rolando provides nifty physical comedy that teeters on the edge of absurdist farce.

The drunken Rolando disrupting Santiago’s sleepy family in Primavera con una esquina rota (Springtime in a Broken Mirror). Photo: Bastián Yurisch.

The action moves across different time periods as past and present collide. Father and daughter play hide and seek – a scene that is unsettled by Rolando and Beatriz growing every closer. These scenes rub against each other, picking up the contrasts and shifts in the dynamic between the trio of friends and Santiago’s family. A music box emerges – one of numerous props imaginatively deployed in the piece; it allows Rolando and Santiago to reminisce about Santiago’s mother’s penchant for music boxes, especially one playing Vivaldi’s “four Seasons” which Rolando and Santiago percussively (and wittily) recreate on stage. Graciela and Rolando’s growing intimacy is captured through the physical proximity between them. From an imposed gulf in the earlier scenes, they later sit and hold hands on the opposite side of the stage to Santiago’s prison cell. Santiago disappears from the stage – increasingly absent from Rolando and Graciela lives. Indeed, Graciela talks of no longer needing him – a painful moment for Rolando who is wracked by guilt.

Throughout, Santiago reads out the letters through which he communicates with his family in exile. Santiago is increasingly isolated as the production progresses. At the commencement, he is one of the cast at the back of the stage but the physical distance between Santiago and his family and friend increases as the piece progresses. Santiago claws at the walls of his cell stage right in angst and frustration. He longs for Graciela and evokes her as he struggles with incarceration. Increasingly as Graciela and Rodolfo move on, Santiago is absent from the action – sidelined both physically and emotionally. Sound is used to conjure a sense of place – radio broadcasts and popular songs transport the audience into a not so distant past.

The staging by Jesús Urqueta Cazaudehore is clean and lean. Reactions are captured by the actors through the most economical of gestures. This is no ossified staging but rather a production that sees history as living and present, something to be shaped and acknowledged. The past must be recognised and owned. At the play’s end, as Santiago appears from the auditorium to face his family there is both fear and love on their faces. All have to face him, to own up to the changes and shifts. The play ends with no resolution; no neatly tied up conclusion. History, lest we forget, is rarely neat.

The novel’s title comes from Santiago’s reflection that the winter of exile will lead to a spring time of freedom that no one can take from him. But the mirror has a broken edge, it isn’t as perfect as Santiago imagines. Spring is less than perfect because reality is always less than perfect. Graciela is flawless when imagined by Santiago – the reality of their relationship shows bickering and banter and power imbalances. This is a story told with candour and passion, and without sentimentality. The histories we inherit are not always easy to navigate.

Ictus have made a feature of “re-presenting” works crafted from an earlier era of the company’s history as productions of the here and now. Director Jesús Urqueta Cazaudehor did this with the 1976 production Pedro, Juan y Diego (Pedro, Juan and Diego) in 2022 and he has now managed it with Springtime in a Broken Mirror. The political events in Uruguay become the site for discussing what was happening in Chile that could not be openly discussed on stage in the mid-1980s. The two countries and their experiences are different but, on this stage, momentarily, they converge to powerful theatrical effect.

The monologues, embodying the isolation and non-communication of the characters that are such a key part of the book, are captured, through the instances of audience address – perhaps best highlighted through the characters of Santiago and Beatriz. Benedetti’s reflections on his own experiences of exile are here replaced by the readings that Camila Oliva Olivos and Nicolás Zárate Zavala make from Damián Noguera’s (auto)biography of his father. Acknowledging the histories we inherit is a key feature of this production where the 1970s, 1980s and the present are in a productive, dialectical dialogue. Ictus may have evolved with Nissim Sharim no longer at the helm, but this important company, based at the Sala la Comedia since 1962, demonstrate that history and theatre cannot be disentangled. This is an ensemble piece, impeccably performed by the cast of six, where actions are shown to have consequences and the personal is always political.

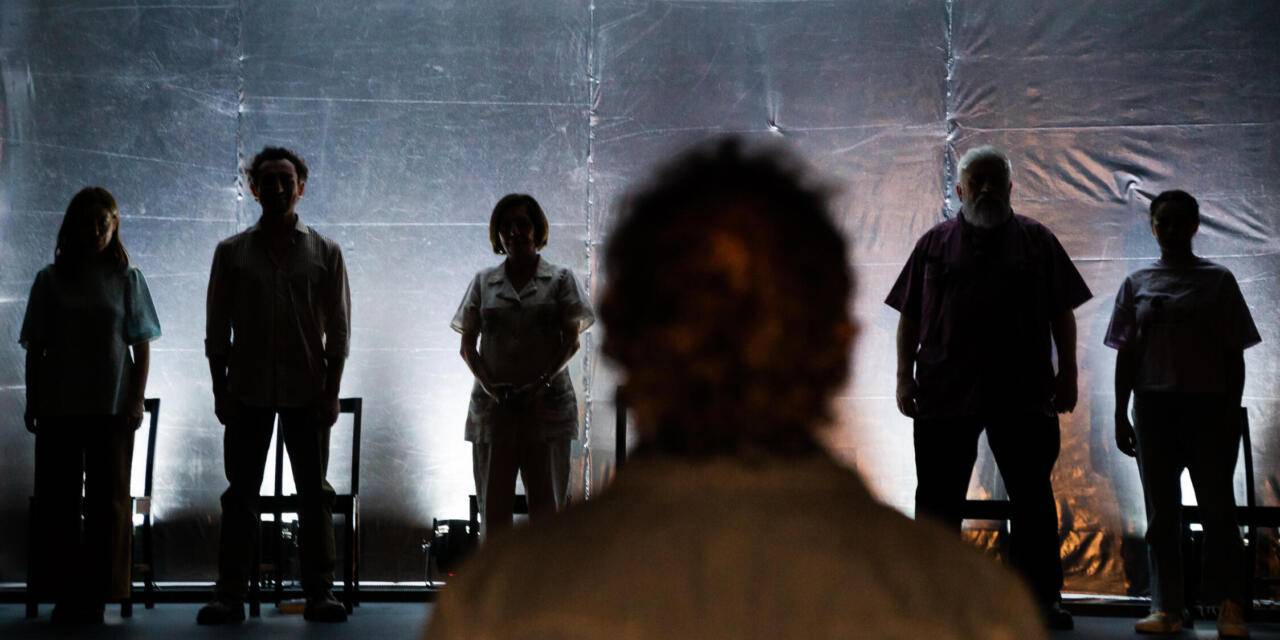

Friendship tested in Primavera con una esquina rota (Springtime in a Broken Mirror). Photo: Bastián Yurisch.

Primavera con una esquina rota (Springtime in a broken mirror) plays at Santiago a Mil 2024 from 16 to 21 February at Teatro Ictus, Santiago.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.