Invisible Lands, a two-performer act, initially presents itself as a nonverbal production with countless tiny props, almost indiscernible for the spectator seated farther away from the stage. The story, however, unfolds in a way that attracts the viewer into an immersive universe that makes the macroscopic surroundings fade.

Revolving around an ever-diminishing group of people seeking refuge from an unnamed, unseen, and almost unheard danger, Livsmedlet Theatre presented the TESZT 2024 audiences with a “cute,” yet disturbing story, taking place on the way of no return.

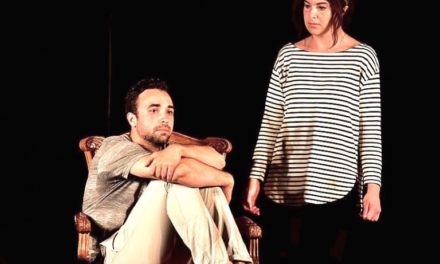

Sandrina Lindgren and Ishmael Falke build not only a world, but an entire cosmos, together developing the image of a God-puppeteer transforming itself into a lesser deity in the eyes of the witnesses. Asleep, yet still able to play with the lives of the littlest of people, this divinity of contrast oscillates between planes, in a constant shift between being awake and drenched in a deep slumber. The body becomes, for them, a literal canvas, taking physical theatre to a whole new level, the breaths and muscle tremors of the performers becoming waves, wind, obstacles in the little characters’ path to freedom.

Invisible Lands, directed, choreographed, and created by Sandrina Lindgren, Ishmael Falke, Livsmedlet Theater (Finland), at TESZT 2024. Photo credits: Alain Baczynsky

The whole production does not, however, stick to a monotonous unity of acting methods, the godly figures undergoing similar situations as the ones they puppeteer, drowning at once with the asylum seekers. This allows for the “puppets” to become part of the audience, the only ones who never take on the part of the mere spectator being the performers. Funnily enough, this is the only role they don’t get to play, although they constantly and always observe what is happening, being confined in the… limited role of God, lesser God, observant God, partial-impartial God, empathic God, yet useless God, unable to save, to fulfil its actual capacity.

The stories of relocation, derooting, re-self-identification, hope are strongly supported by the linguistic soundscape of the production: “nonverbal” as in “unintelligible”, the invented language of the characters alluding to both Arabic and Finnish and broadening the background of the plot. Remnant of the imaginary world of a child’s play, the modulated gibberish complements the minimal set design consisting of toys, scalable replicas of real-life objects, and painted bodies. The actors strip, to accommodate the evolution of the storyline, their initial costumes reminding of scouts’ and/or school uniforms being replaced by skin, folding and twisting at once with the tumultuous odyssey.

Invisible Lands, directed, choreographed, and created by Sandrina Lindgren, Ishmael Falke, Livsmedlet Theater (Finland), at TESZT 2024.

Following the same pattern of the “pretend” games played by kids on a spring afternoon, the two creators imaginatively integrate technology in their set design, using a stapler painted in white and hidden in plain sight as a clapperboard to give cues for the music and voice recordings to stop or commence. The blankness, thus, not only enhances, but also conceals, the white stage floor doubling, towards the end, as a secondary canvas, highlighting the only traces of the [any!] show actually taking place.

The very tiny figures make it difficult to follow – exactly like when you are detached from the real story, when you only read about it or see it on the news, it is difficult to see, to relate, although it is as real as could be. This strong visual decision of reducing the size of the characters to maximum a couple of inches also diminishes any possible racial differentiation of the figurines, thus forcing the spectators to bend, squint their eyes, overall develop a higher acuity of their senses, for the sake of the production’s active reception. A skilfully directed addition to the size-determined aspects, the figurines form a constantly collective character, with “voices” gaining individuality from time to time but returning to the “general panel” and re-turning the narrative to the generally-valid story of migration, risk, life-and-death matters.

A tale of migration, a contemporary odyssey, too familiar to the audiences, loses any pretentiously political character – it is no longer a speech, an interview, a statement, but rather a raw close-up to what is, in fact, lost on the way to freedom and safety, childhood, play, innocence.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Teodora Medeleanu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.