The topic of the digital spectator and, implicitly, the one of the multi-stratified co-presence, with all of the implications that arise from such an encounter with a production or with a performance, was not a privileged one in the Romanian space, a theatre landscape that inherently connected to a theatre of the word that only later on discovered the temptation imposed by the use of technology and media as an organically integrated part of an artistic product. I have discussed at large, with a different occasion, the causes of this cautious relationship Romanian theatre makers have with technology and their availability to accept new forms, redefinitions of theatricality, possible redimensioning of the status of spectator[1]. I will not reiterate them here, but will simply observe that it was only the Pandemic that made us reflect, experiment, and imagine, with an unsimulated seriousness, a possible surpassing of the traditional paradigms. The first book published in Romanian on the topic of the intersections between Romanian theatre and new media has only been published in 2020, therefore during the peak of the pandemic crisis, and it catalogues a series of timid initiatives of certain autochthonous creators in the field of new technologies (Cristina Rusiecki, Un click și …1000 de realități. New media în teatrul românesc [One Click and… 1000 Realities], Bucharest, 2020). We were, and still are, deficitary also in the case of translations of international writings relevant to this topic, our only references being the ones collaterally approached by Hans-Thies Lehmann in his Postdramatic Theatre.

Although during the last two years significant progress has been made in this direction, for most of the theoreticians and practitioners from the Romanian theatre environment, the subject remains a niche one, with a great degree of abstraction even for the younger ones, the iGeneration from whom everybody expects the great revolutions of the performing arts field. For this perspective, is notable a study of William W. Lewis, where he synthesises a series of recent theories that converge towards the idea that the extreme familiarity with the internet profoundly and irreversibly modifies the relationship we have with the world. The habit of accessing information through hyperlinks creates, in turn, optimal conditions for a new type of spectator: one that, just like in video games, wants to be involved in all the levels of what they see: in terms of playwriting, directing, performance etc. The generation born after 1990 (iGen) already has the genetic mark of a new type of relationship with technology (iDevices), and this cannot leave the status of spectator unaltered. Within a behaviour dominated by multitasking, the classical audience’s passivity needs to be surpassed by a so-called “audience-centered performance” inside an “interactive theatre”: “In interactive theatre, the audience becomes the center of the performance as participant, observer and author, thereby changing the focus of theatrical storytelling and performance from making something seen into something experienced”[2]. We are still not ready for integrating in our usual theatre vocabulary terms such as “posthuman spectator” or “postorganic fields”, used since the 2000’s in the international theatre world[3].

I have, several times, experimented with the part of the “digital spectator”, in those hybrid productions that fuse theatricality with film, developed during that heinous lockdown with a sort of desperate innocence some Romanian creators had to oppose the almost morbid passivity that theatre was in. The online co-presence was strange for the couple of dozens of people who were forming the audience and who, out of curiosity, accessed the links they had previously received. I remember, even now: all of us were aware of the others’ presence, we could see our names on the list of people who were attending; I could recognise some of those names, critics or artists, whom I, unfortunately, could not greet in this ambiguous foyer where I was “walking around” cautiously, on my own. The live performances were, generally, no longer than one hour. I was watching them distantly, not being able to connect emotionally, the last half of the hour finding me stranded, in a bizarre form of performative wandering. Retrospectively, I became aware of the fact that there was nothing related to passion that was making me be there, in that uncertain live streaming, being in for ghostlike co-presences, as in a digital Elsinore where I could hear voices, register images, recognise actors who were trying their hardest to commit to their new stage practices. I was there rather out of solidarity with those who chose to do something instead of nothing at all. I still associate the status of “digital spectator” with that time of restrictions, of anguishes, of news about the sudden death of certain acquaintances of mine; this is the reason why, for me, at least, being a “digital spectator” has certain traumatic hues. I believe I am still to acquire that distance, needed in order to speak about such things with certain detachment. How could I get over the fact that, while I was experimenting with trans-physical encounters, the manager of the Suceava Theatre, one of my best PhD students, was living the last moments of her life?! How could I not associate these digital experiences with the disappearance of some of my colleagues from university?! How could I speak objectively about my perceptions from when theatres were closing and artists were brought to their knees financially, when the scandal between the vaxxers and the anti-vaxxers was reaching alarming levels, when the society was torn apart by panic and, for most Romanians, thinking about art in such times “of war” was something almost perverse and vulgar?!

Oedipus the King, ”Marin Sorescu” National Theatre Craiova, Director Declan Donellan, photo credit – Florin Ghioca.

During such a period, organising the National Theatre Festival, the most important yearly event in Romanian theatre, became “mission impossible”. I had already accepted, since late spring 2020, the offer to be one of the three curators of that year’s edition (alongside my colleagues from the National University of Theatre and Film from Bucharest, Ludmila Patlanjoglu and Maria Zărnescu), sincerely hoping that, in the summer months, the pandemic will become just an awful dream from the past. It was only later, in September, when we understood that the physical “co-presence” of the virus was far from over. We were faced with having to choose between putting on hold a 30 year long tradition (the Festival was also celebrating a round number, therefore the pressure of organising it was even stronger) or going for this exact type of online co-presence, moving the entire Romanian theatre on the laptops, tablets and the other devices of our participants and audience. Together with Ion Caramitru, the President of the Romanian National Theatre Union, manager of the National Theatre of Bucharest, and, at that time, the most influential figure in Romanian theatre, we opted for continuity. For the first time in its history, the Festival was to be held entirely online, for eight days, in November 2020. We developed it following two major directions: one of them was that part of the festival did not require live online attendance, allowing the audience to revisit the archive recordings of major Romanian productions that marked turning points in the last half of century – this made us realise how vulnerable our national archive is, but this should be detail in another discussion; symbolically, we tried to establish a co-presence with our recent theatrical history. In the second direction, the festival had the ambition to bring into discussion (during online debates) what was happening to us and analyse from an aesthetic perspective, not lacking any form of shyness, the new hybrid formulas and the new conditions of the spectatorship[4].

The effects of this were also under the sign of hybridity: on the one hand, there was the nostalgia of the video reunion with the productions and the artists from the past, attended by a couple hundreds, even thousands of people who accessed the platforms of the Festival during that time; on the other hand, productions such as Zoom Birthday Party (Saviana Stănescu), Live (directed by Bobi Pricop), Pool (No Water) (Radu Nica, Andu Dumitrescu, Vlaicu Golcea), brought together under the title of “Aesthetics of the Pandemic”, obliged us to revisit and reevaluate, in a honest manner, concepts such as “the essence of theatre”, “presence”, “digital audiences”, but also the interventions of new technologies in the venerable art of theatre. The general note of the discussions was, as I remember it, dominated by raising unsettling questions and the refusal or the delay of providing definitive answers to them. The positions taken were frequently radical ones: from outrightly denying the new theatrical aesthetics and dispatching them to the area of “temporary solutions in times of crisis”, to calls regarding what was considered to be an excellent occasion to relaunch and refresh a form of art that is showing certain signs of weariness. The status of “digital spectator”, however, did not entirely satisfy anybody, not in the case of the solitary digital spectator, nor when the screen was shared with other members of the digital audience.

Cenci Family, ”Vasile Alecsandri” National Theatre Iasi, Director Silviu Purcarete, photo credit – Bogdan Andone.

One of the dilemmas that we were facing at that moment – problem whose final solution seems to be awaited to this day – was related to the impossibility of defining, in terms of public and private, the virtual space we were in. The online co-presence and the manner in which we were perceiving one another as digital spectators were clearly influenced by transgressing the traditional and the friendly public-private relation. Most of us were taking part in these events from our own homes; looking at each other, we could see fragments of their private spaces: the corner of a wardrobe, a title on the spine of a book from the shelves in the background, a clothing item carelessly left on the armchair that was in the visual range of the video-camera, another member of their family awkwardly passing through the room; simultaneously, our private spaces were co-existing within a virtual public space. The feeling was strange: it was as if we had met in a theatre hall while dressed in our pyjamas, ready to go to sleep or having just woken up. Perceiving the other was done in a manner defined by an unpleasant familiarity we tried to surpass by resorting to humour… a very compelled one. The audience members who belonged to the academia already had experience with this “beyond public and private” feeling and, on account of this routine, were showcasing an additional level of state of relaxation. In the case of most people, however, perceiving the online artistic act was clearly affected by the incapacity of defining the space they were in.

The co-presence in the online environment became even more problematic when the people who make up the audience could not have seen one another, either because the list of attendees was hidden by the organiser, or as, due to shame or any other reasons, the participants turned their cameras off. They can see, but cannot be seen in return, situation that is responsible for unbalancing the rather complex democracy of sight-in-theatre. At once with one of the participants’ cameras being turned off, the presence and the feeling of one’s presence in the other’s mind was considerably diluted, tending to auto-cancelling; new theorization fronts arose in regards to these diffuse presences. For anyone who has ever held a class online, the psychological reflex to only address the ones they could see is familiar, the rest of the people in the class, reduced to icons lacking visual identity, entering an ontologically ambiguous level of “present absences.”

Subsequently, I believe that the lack of interactivity between the spectator who was online and the performance they were watching represented another issue. Specifically, we were implanting a specifically on site behaviour to an environment that was requiring a completely different type of attitude, we were bringing old habits to a new setting and expecting them to be entirely functional. It was just as if, armed with a hammer and a pair of pincers, we tried to repair the motherboard of a state-of-the-art computer… This is, in fact, the difference between the classical psychological interpretation act that the traditional audience performs from their chairs and the active interpretation, the one that stands as a form of intervention and that the new theatricalities seem to claim as a necessity. ”The audience member’s contribution is primarily mental. Comparing video games and theatre, Daniel and Sidney Homan (2014) explain: «Serious plays, whether comedy or tragedy, have always acknowledged the importance of the spectator as a player in the action onstage, at times offering this significant player a self-image». The stage spectacle offers spectators the ability to play along, but only in their minds. This readers/ spectators sit and watch, interpreting the visual and aural information presented in front of them as a form of textual and symbolic decoding (…) In contrast, in audience-centered performance the design of the overall structure transforms «the role of the spectator into a participant and even a performer»”[5]. An example for such a structure, interactive and audience-centred is Operation Black Antler, initiated in 2016 by the companies Hydrocracker and Blast Theory, “an immersive theatre piece that invites you to enter the murky world of undercover surveillance and question the morality of state-sanctioned spying”. (https://www.blasttheory.co.uk/projects/operation-black-antler/). The innovations in this field are, actually, even older, a trailblazer in this regard being Eduardo Kac, who set the theoretical basis for “transgenic art”, with performances such as Genesis (1998) or Uirapuru (1999). “The telepresent spectator of Genesis is offered the opportunity to engage in the switching on of the alteration technology. They are not witness to, nor are they required to take responsibility for, their actions.”[6] It is exactly the absence of the interactivity that generates a feeling of loneliness that the online audience has to face from behind the device on which they connected to the performance, regardless of the fact that they know, without any doubt, that, at once with them, tens of other people are also there, simultaneously watching the same piece, together[7].

The Homecoming, ”Matei Visniec” Theatre Suceava Director Botond Nagy, photo credit – Luana Popa.

The 2020 edition of the Romanian National Theatre Festival was one beyond success or failure, following the meaning of Nietzsche’s “beyond good and evil”; taken as a solution in times of crisis, it was the ambition to organise it that deserved the applause, rather than the actual contents of the event. Today, the people of the theatre world see it as a necessary parentheses, but one about which it is better to talk as little as possible.

In 2021, a different curatorial team decided, at the last minute, to keep the festival in an online form. The reasons given for that were, rightfully, the pandemic’s unpredictable nature – only one actor catching Covid blocked the entire team and made the performance entirely inoperative – and the severe financial incertitudes caused by the place art and culture occupied on the Romanian Government’s list of priorities (where health was the first, as expected). The fact that theatres had started to professionally film their productions was used in the favour of the curatorial team, as they, indeed, had something to put on display for this year’s new online edition. The access was going to be free of charge. The reaction Romania’s theatre spheres had in regards to the news that the festival was going to be held online once again was, however, one of fierce disappointment, many of them having expected that the return of on site events would represent a bold statement of the live theatre that never surrenders. The passing of Ion Caramitru, the president of the Romanian National Theatre Union[8], in September 2021, destabilised the decisional structures of our country’s theatre even more. The audience no longer seemed willing to experiment within the limits of the role of digital spectator, the artists were lacking any form of stake, and the theoreticians either exhausted all of the possible new theatrical theories they used to be so fond of, or had gotten bored of them. There was not much that was said or written about NTF 2021[9], an online project that seemed to have rather turned the audience hostile in regards to theatre in its digital form, instead of continuing getting them acquainted with it, process that started in 2020.

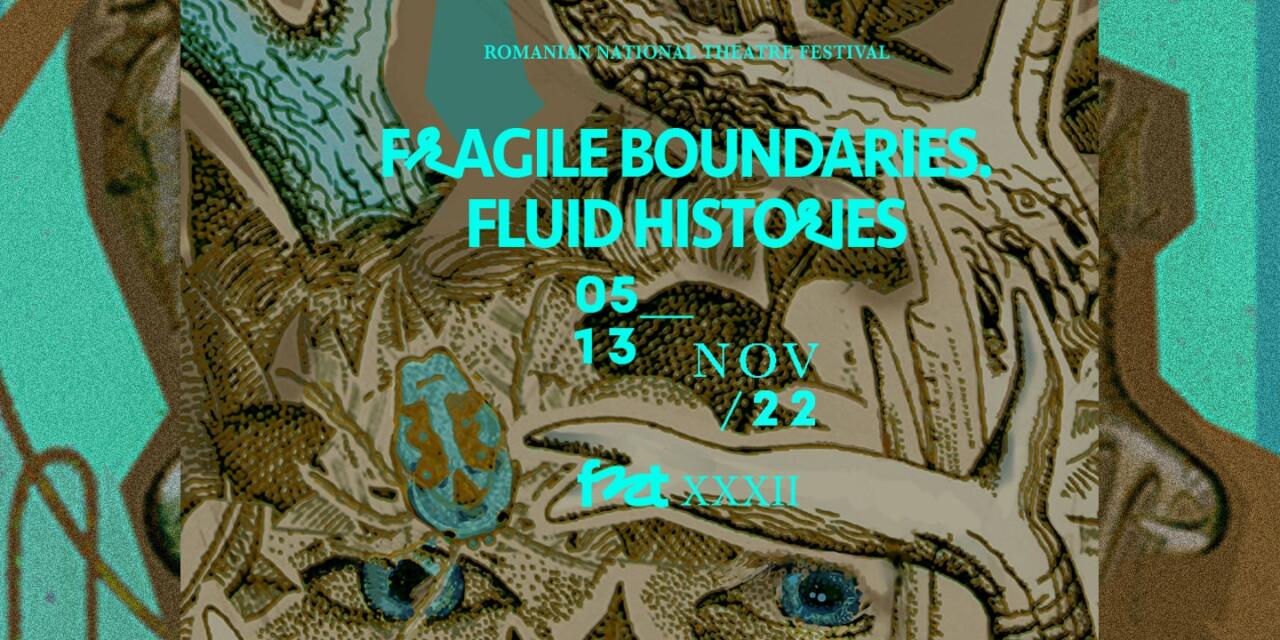

The certainty (not devoid of fear, as a war is taking place at our borders) that the National Theatre Festival will take place on site in 2022 convinced me to accept, with a cautious enthusiasm, a new curatorial mandate (together with Mihaela Michailov and Oana Cristea Grigorescu). At the time when I am writing these lines, more than three weeks have passed from the 2022 NTF. The considerable success of this year’s edition is explainable, most importantly through the general excitement of the audience to come back to the classical, physical co-presence. Most of the guest productions were already sold out in just a couple of days (in some cases it was even a matter of hours) after the tickets had been put up for sale. Many of the participants mentioned a new atmosphere of the Festival, one marked by a serene, bright, friendly relief. A very well known Romanian director admitted, during the Festival, that he had gotten back on good terms with people he had age-long conflicts with. He said this need for reconciliation was based on the atmosphere of this year’s edition. Other artists confessed that, also during the Festival (which took place in November) they had the feeling that we were in spring. The good weather conditions contributed to that, certainly, however, beyond the limits of meteorology, I believe it was, more or less symbolically, about something that was perceived as a rebirth or a renaissance. This did not happen only thanks to the curators’ work, but rather as a result of that feeling of tense wait for something that had been missing for the previous two years and that, this time, was defined by alleviations, by the discharge of this tension. The NTF seemed to be a generous Godot, appearing smiling to those who had been waiting for him for so long. The old aesthetics of the reception theory (Wirkungsästhetik), brought into discussion by Lessing, confirm once again, in moments such as these, their legitimacy and, moreover, their implacable nature[10].

The Seagull, National Theatre Bucharest, Director Eugen Jebeleanu, photo credit – Florin Ghioca.

During the preparations, one of the issues we faced, as curators, was related to a possible online part meant to accompany the on site one. Initially, we intended to double the selection of live performances with several productions we wanted to also broadcast digitally. We were mostly taking into account the stagings that had a strong hybrid component, were going beyond classical theatre’s limits, or were opening a gate to technology and to aesthetics that were still tributary to the influence of the pandemic or that were even inspired by that. Still, almost tacitly, we ceased talking about the online aspect, as if it had been a person we had no quarrel with, but about whom we simply avoided speaking. Only now, after the end of the Festival, I realise that, in fact, we were afraid to not alter the absolute joy of coming back to the physical co-presence. We only chose a limited number of online events (including a debate about Peter Brook, that took place online due to practical reasons – the impossibility of George Banu’s arrival in Romania).

In what concerns me, reinstating the physical co-presence in theatre halls validated once again a supposition that I have had for a long time: an extensive part of the way in which a spectator relates to a production is inherently connected to the reactions of the other audience members and it heavily depends on behavioural aspects they borrow from, trade with one another, during the performance. Never have our interpretations, or the ones of the people around us been pure, they always are contaminated by what we feel the others might be feeling. In a more or less subtle manner, we allow ourselves to be influenced by the contagious laughter, by the apathy, or, on the contrary, by the enthusiasm of those around us. Sometimes, these details become uncomfortable, they bother us, disturbing what we believe to be our direct, individual relationship with the performance. Yet, we must admit that the invisible network of the relations between the spectators, parallel to the one between the characters on the stage, influences our final attitude towards the artistic act. The physical co-presence of the other discreetly infiltrates the personal interpretational methodologies of each audience member. This physical co-presence of the other, whether we like it or not, draws the contours of our private hermeneutics, through which we decide if we liked something or not, if it touched us or if it cut no ice with us, right there, in the theatre hall. The well-known image of a lady looking through opera binoculars at both the stage and the rest of the audience becomes a reasonable metaphor of the complex acts of communication that exist amidst the people who attend an event.

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, ”Andrei Muresanu” Theatre Sfantu Gheorghe, Director Radu Nica, photo credit – Volker Vornehm.

I believe that, indeed, experiencing the online co-presence helped us not only value more the older social rituals associated with going to the theatre, but also understand that, as tempting as adventuring in the digital world might be, we are not yet ready to abandon gestures, contents, habits, manners of perception that are so deeply rooted in us; the promise of a digital catharsis appears as a distant shadow, just as only few are willing to trade the old feeling from a theatre auditorium with the “digital emotions” from an unlikely pixel world. The major turning point from the latter part of the XXth century brought about by the so-called postdramatic theatre had never threatened the central pillars of drama; be it noted, incidentally, that, in comparison with what the pandemic proved us to be alternatives of the old performing arts, postdramatic theatre seems to be, today, something remarkably well-behaved and conformist…

The two years of restrictions we had were too short of a time to dangerously destabilise the grand internal structures of the spectator; these two years only opened a window to look through – perhaps towards the future, perhaps towards a parallel reality -, although for many this gate is already closed, even definitively sealed, walled in, forgotten. Beyond any other theorisations of a physical co-presence in a theatre hall, we must admit our dependence on what Grotowski defined through “encounter”, in the most factual sense of human bodies, self-aware ones, that exist together in the same space, in order to take part, through a powerful ritual of retrieval, in the great encounter with art. The breath of the other, their perfume, the hazy silhouettes that comprise this “cherry orchard” the audience is, the rustle of their restrained moves, the feeling of energies that are impossible to render – all these, we must admit, are so difficult to replace… Still so difficult…

This text was written with the support of Between.Pomiędzy Research Group.

Calin Ciobotari and Matei Visniec at the presentation of the book ”A History of Kissing in Theatre”, National Theatre Festival, Bucharest 2022. Credit photo: Luana Popa.

References

Causey, Matthew, Theatre and Performance in Digital Culture, Routledge, 2006

Fischer-Lichte, Erika, Wihstutz, Benjamin (editors), Transformative Aesthetics, Routledge, 2018

Fliotsos, Anne & Medford, Gail S. (editors), New Directions in Teaching Theatre Arts, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018

Hertz, Noreena, Secolul singurătății. O pledoarie pentru relațiile interumane, translated by Simona Maria Onciu, Humanitas Publishing House, Bucharest, 2021

Kemp, Rick, McConachie, Bruce (editors), The Routledge Companion to Theatre, Performance and Cognitive Science, Routledge, 2019

Rusiecki, Cristina, Un click și …1000 de realități. New media în teatrul românesc, Bucharest, 2020

Critical Stages, Issue No.25, June, 2022

Footnotes

[1] See Călin Ciobotari, „Who’s Afraid of Technology in the Theatre?”, in Open New Tab. Theatre and New Technology, Junimea Publishing House, Iași, 2021.

[2] William W.Lewis, “Approaches to Audience-Centered Performance: Designing Interaction for the iGeneration”, în Anne Fliotsos & Gail S. Medford (editors), New Directions in Teaching Theatre Arts, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, p.10.

[3] See, for example, the section entitled “Posthuman and postorganic performance”, in Matthew Causey, Theatre and Performance in Digital Culture, Routledge, 2006.

[4] The programme for this respective edition can be consulted here: https://fnt.ro/2020/program29nov/

[5] William W. Lewis, op.cit., p. 14, 16.

[6] Matthew Causey, op.cit., p.147

[7] The question of the loneliness behind the screen is detailedly analysed by Noreena Hertz in Secolul singurătății. O pledoarie pentru relațiile interumane [The Lonely Century], translated by Simona Maria Onciu, Humanitas Publishing House, Bucharest, 2021, “Our Screens, Our Selves” chapter (pp. 111-152)

[8] The Romanian National Theatre Union (UNITER) is the producer of the National Theatre Festival.

[9] The programme can be found here: https://fnt.ro/2021/program-14-nov/

[10] An excellent mirroring of the aesthetics of the spectator’s reception of the performance (Lessing) and the aesthetics of distancing (Goethe și Schiller) is found in Erika Fischer-Lichte and Benjamin Wihstutz (editors), Transformative Aesthetics, Routledge, 2018, pp.1-25.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Călin Ciobotari.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.