This article is brought to you by Hong Kong Arts Festival.

We know that what separates humans from other mammals is our superior brains. What separates humans from machines in the era of artificial intelligence? It’s increasingly up for grabs. You’d expect a panel of scientists, some Silicon Valley heavyweights and maybe a philosopher or two to examine the question. But what if the best argument was made by a literature Ph.D. and a few theatre nerds?

That’s the dream team behind To Be A Machine (Version 1.0), the not-to-be missed motherboard of Hong Kong Arts Festival’s digital programme in March. The team consists of Mark O’Connell, author of the award-winning book To Be A Machine: Adventures Among Cyborgs, Utopians, Hackers, and the Futurists Solving the Modest Problem of Death; Bush Moukarzel and Ben Kidd, co-directors of the Irish experimental theatre company Dead Centre; and Game of Thrones star Jack Gleeson. It’s a seriously theatrical reflection on what it is to be human and it throws a body block at the rapidly advancing future of mind-uploaded consciousness.

Ben Kidd & Bush Moukarzel. PC: Lucas Beck

Such a future is the subject of O’Connell’s book, which introduces ordinary mortals to the techno-utopians who fall along the spectrum of transhumanists, or believers in a movement pioneering technologically aided, physical and cognitive enhancements aimed at extending human life. Among these are the Google AI wizard Ray Kurzweil, who has long heralded the coming of the “singularity” or the time when AI will surpass human intelligence; Max More, the guru of cryonics, the practice of deep-freezing corpses until technology can revive them or at least exploit what remains; and Tim Cannon, who is on a DIY quest to become a cyborg by implanting heat sensors and magnets into his body. While some transhumanist ideas are already in the mainstream—Cannon’s “biohacks” are not much different from pacemakers, contraceptive implants and other familiar tech tools used in modern medicine—O’Connell likens these futurists to members of a “liberation movement” whose objective is “nothing less than a total emancipation from biology itself.”

Mark O’Connell. PC: Richard Gilligan

Their machinations leave Moukarzel and Kidd cold. During a Zoom call from Dublin, the pair politely dismiss the transhumanists’ quest as the dystopic wet-dream of Silicon Valley billionaires: all tech and no sex, or to metaphorise from tech, no “noise.” But it is noise, precisely, that drives Dead Centre: “all the kinds of ancillary information that swirls around the culture,” Moukarzel explains. If the transhumanists inspire anything for them, it’s “the fallout of these technological ambitions, what it might feel like to be in a world where all this is happening.” With the pandemic bringing technology more intimately into our lives, from Zoom avatars to Covid tracking apps, that noise has recently hit a fever pitch. Luckily, O’Connell has a ”way of rendering some of the stranger parts of life funny [that showed] an affinity with the way we try to build atmosphere on stage,” says Moukarzel. It was, in short, “the opportunity for a theatre show.”

As he speaks, Moukarzel is seated on his couch with his Pomeranian beside him and a huge, wall-mounted fan the colour of toasted butter positioned directly behind his head, so that his bearded face appears crowned by a radiant halo. Playing Lucifer perhaps to Moukarzel’s Christ, Kidd tugged his hair into razory spikes throughout the interview like a tormented demon. As much as O’Connell digs into the quasi-religious yearnings of the techno-utopians who are looking to cheat death, the joined minds of Dead Centre have their own church of sorts, whose mission is to bring forth a communion between theatrical form and content, actor and audience.

Their interests veer towards deconstructions of classics that run deep enough, or are just flawed enough, to accommodate their probing inquisitions, from Souvenir, which shot spit balls of 21st century angst at Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, to Chekhov’s First Play, where a wrecking ball smashed the period decors and an audience member was enlisted to play the starring role. To Be A Machine (Version 1.0), created during Ireland’s first Covid-19 wave in 2020 for Dublin Theatre Festival’s digital edition that year, is their most audacious show to date; it transubstantiates a remote audience and the abstracted humanity that they conjure into a viscerally sad meditation on absence and death.

That sounds gloomier than it is. The descriptor Moukarzel and Kidd frequently use for their methods is “playful,” as a shorthand for the curiosity and resourcefulness needed to create thoughtful, compelling theatre on a par with live performance in the midst of a pandemic. Live streaming a play to an invisible audience just because theatres were shut didn’t interest Moukarzel and Kidd until they struck on “a slightly quirky and naive, playful interpretation of what a lot of the transhumanists espouse,” says Kidd.

Jack Gleeson. PC: Ste Murray

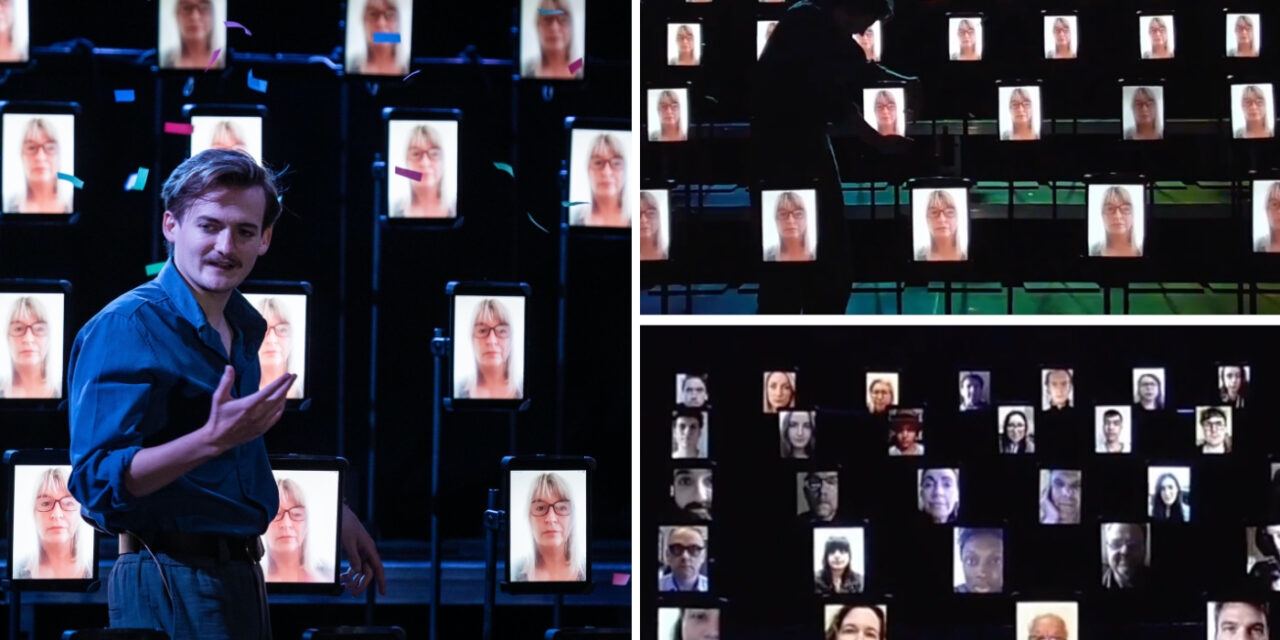

That was the idea behind asking ticket buyers to pre-record their faces and for their videos to be individually uploaded to iPads spaced along tiered rungs facing the stage, a lot like an audience would appear in its house seats. At showtime, while Gleeson expounds on Kurzweill’s theory that we’ll soon be able to transfer our complete cognitive data into computers that will “live” as our steel and plastic proxies, or explains More’s cryonics lab, where clients pay to have their heads severed and embalmed in liquid nitrogen when they die, audiences encounter their own disembodied faces on the iPads and watch as these seem to follow the performance independently from their own bodies at home.

From Dead Centre’s perspective, the challenge of performing to a remote public “seemed like a really interesting opportunity to make the audience wonder about what they’re doing when they are in a theatre,” says Kidd. Thematically speaking, it’s a startling use of quotidian technology that instantly materialises transhumanism’s existential problem of being a person without a physical shell.

It also underlines the paradox that is at the crux of O’Connell’s clear-eyed observations of the transhumanists: the cutting edge of futurist pursuits is predicated on a 17th century paradigm that is largely discounted today, namely Cartesian mind-body dualism – I think, therefore I am. In one of the many dumbfounding anecdotes O’Connell relates in his book, he describes what a contemporary manifestation of this position can look like, which he located in a YouTube video from 2006. In it, a young Swedish academic celebrates a campy dark mass to the power of Almighty Data, arms outstretched and solemnly intoning thus: “‘Around me shines the bits and in me is the bytes. The data, the code, the communications. Forever, amen.’”

Dead Centre’s men are cut from theatre’s cloth, however, and in their hands, the dualism question naturally focused on actor/character duplexity. To dig into it, Moukarzel and Kidd turned to Gleeson, who has spent nearly as much time playing Joffrey Baratheon on Game of Thrones as he has putting that evil boy king behind him. As it turned out, he “hit the sweet spot for this kind of live/film/stream/theatre/hybrid event,” says Moukarzel. In Gleeson, who also holds degrees in philosophy and theology, they met another theatre nerd who was keen to “get into the headspace” of the transhumanist identity crisis, plus a little of his own, playing O’Connell as a version of himself, who is also Baratheon, etc. “In a very simple, charming, poor theatre kind of way,” to borrow Moukarzel’s words, it works. That is to say that, without trotting out the ghost in the machine trope that is a cliche of sci-fi, it leaves us to mull the central questions of this pandemic inspired show: When our bodies become biohazards, isn’t it more comforting, safe and expedient to let technology “be” us? What do we lose if it does?

But this too shall pass. Now that most countries have mounted sufficiently robust immunity and the anti-Covid clinical tools to be able to discard social distancing restrictions, To Be A Machine (Version 1.0) has become redundant and will have its final curtain call at Hong Kong Arts Festival. “Its meaning is getting to its sell-by date” Moukarzel admitted, explaining that performances in Paris in December failed to draw audiences away from the live concerts, shows and nightlife that were finally on offer again. “The whole premise of the show is that you can’t do those things. So, unluckily, it will work in Hong Kong.” The conversation pauses a moment at the thought; has a Covid-obsessed Hong Kong become the last place on earth where so-called lockdown theatre can still survive, in a cryonic bath of hand sanitizer and Sinovax?

There is still the possibility that a version 2.0 may be in the works for live audiences, somewhere else in the world. Pandemic or not, the transhumanists’ quest is not futuristic so much as it is timeless, in a long line of quest narratives “about where do we locate the essence of the human,” says Kidd. “It calls to mind for us an age-old yearning to transcend the body, for immortality, the fear of death,” adds Moukarzel. “These things are universal and we can speak about them now and always.”

Let those of us holding on in Hong Kong hope so. The alternative may have to be a time and space defying escape to a mind-uploaded future. But if the time comes, amen to that.

This article was originally published by ZolimaCityMag on March 17, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.