This is the story of the Big Bang. Not the explosion that gave birth to the universe. But an explosion in a mine in the Czech town of Karviná (Czech Silesia) near the Polish border. From that explosion was born a universe of pain, as described by Karin Lednická, a native of that town and author of the bestselling book, Leaning Church. This story is written in black and white; literally charcoal on the blackened, whitewashed pages of a history that many would rather forget.

The program of the 10th-anniversary edition of the Madách International Theatre Meeting (MITEM) included an entire festival – Synergy World Theatre Festival – in its “theatre embrace”. Within the framework of this event, Budapest has brought notable theatre productions from different years, united by the theme of linguistic and ethnic minorities. These very different genres and moods are accompanied by subtitles in Hungarian and English, for which, however, the sound of the word in the mother tongue is very important. In translation, as usual, much is lost and weathered, but the live word heard from the stage, even in an unfamiliar language, adds a special aura to the audience’s perception of the production. Leaning Church, directed by Radovan Lipus, is a production of the Czech theatre Těšínské divadlo in Český Těšín, a unique theatre where two ensembles performing repertoire in both Czech and Polish languages meet. The Polish troupe is oriented towards the Polish population of the Czech Republic. The theatre also has a children’s studio, which plays in both languages. The bilingualism of the theatre is connected with the bilingualism of the city, which survived the territorial division between Poland and Czechoslovakia in 1920. After the new border was drawn, the territory of present-day Český Těšín became part of Czechoslovakia. The population here is mixed Czech-Polish, and the main task of the theatre, established in 1945, was to serve the audience speaking both languages. The Polish theatre was founded in 1951.

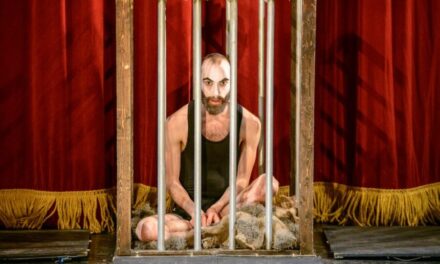

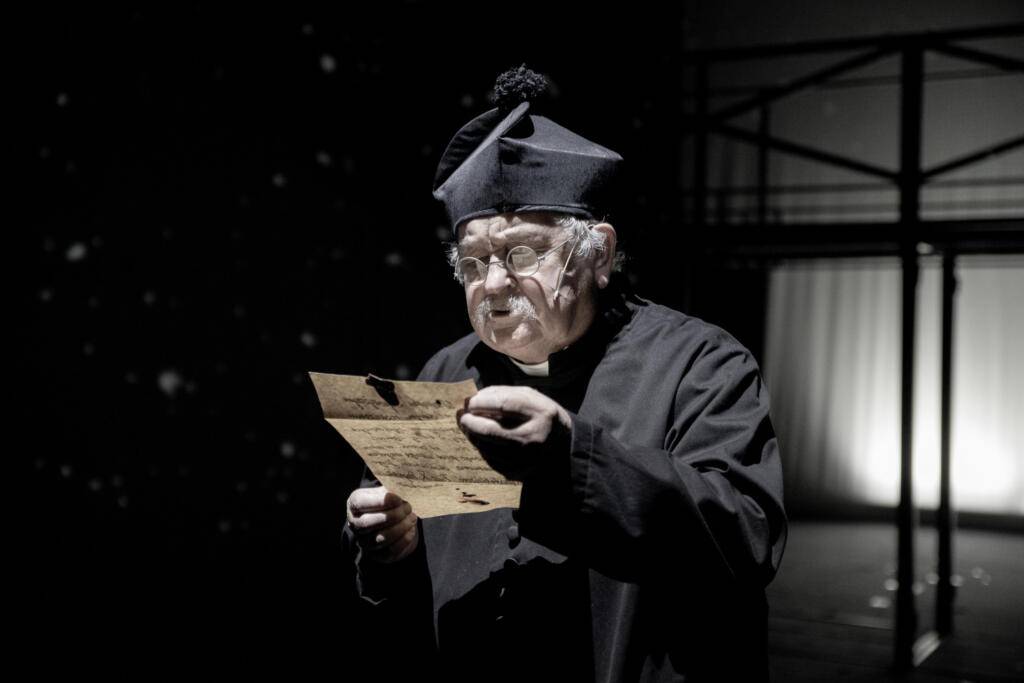

Photo Courtesy of Těšínské Divadlo Theatre.

Karin Lednická’s novel is in perfect harmony with the super-task of this theatre. The novel is partly about the Czech-Polish conflicts that arose after the collapse of Austria-Hungary. The play, however, focuses on universal human manifestations and destinies, as well as the human ability to withstand difficult situations, rather than primary national manifestations and grievances. The novel-chronicle takes the historical background in a detached and cold manner, favoring no one – the first part speaks of the pain inflicted by the Czechs on the Poles, and the second looks at the offenses the Poles took against the Czechs although here there are no victim complexes, no accusations and mutual recriminations. The novel is written neither from the Czech nor from the Polish perspective. It is as distanced as possible and the fact that the novel, written in Czech, is played in Polish becomes another contribution to the corpus of knowledge, understanding and reconciliation, which is hard to overestimate. Here is the fate of a man against the backdrop of the fate of a city, a country, and the world. This story is, in fact, a work in progress – it opens the pages of common Czech, Polish, and Soviet history without seeking to retouch unpleasant and painful moments.

Photo Courtesy of Těšínské Divadlo Theatre

Leaning Church is conceived as a trilogy. The author has published two books dedicated to the town of Karviná, whose history and vicissitudes reflect world history. The first part of the trilogy covers the period from 1894 to 1921, the second from 1921 to 1945. The third part, according to the author, will end in the 1960s and 1970s, when the city underwent the greatest destruction. Radovan Lipus’s production, masterfully staged by Renata Putzlacher (also the author of the translation), is based on the first part of the trilogy and tells the story of a mining family at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The predominant color of the performance is black. The light of miners’ lanterns illuminates separate fragments from the mosaic of one town’s fate. Coal was once the glory of this town. A century later, it also led to its decline. Nothing remains of its former prosperity and respectable buildings. The tilted, shriveled church reminds sullenly and reproachfully of the events of the past. Church św. Piotra z Alkantary and the Karwina cemetery, where 235 victims of the explosion at the Franciszka mine and later at the Jan-Karol and Głęboki mines are buried. Miners’ widows and orphans, small people against the backdrop of great grief are the heroes of the novel and the play based on it.

Projections on the walls of the set, shadows, halftones, and a gloomy feeling of memories waking up from a long sleep – this is the atmosphere of the performance. These are the unburied, unmourned pages of memory, the pages of history. In this complex plot with many characters and intertwining stories, three indomitable Barbora (Małgorzata Pikus), brave Julka (Barbara Szotek-Stonawski), and clever Ludwik (Kamil Mularz) stand out, illustrating three models of human behavior in circumstances where life tests us. Some surrender by submitting to circumstances, others try to overcome tragedy by trying to make the best of it. But no matter how fussy a person is, history harshly and unceremoniously interferes with his plans.

Photo Courtesy of Těšínské Divadlo Theatre.

While watching this play, you catch yourself with horror at the thought that it is based not on the author’s artistic imagination, but on real events. It’s a very cinematic production and story (there will probably be a film version of the trilogy as well), which is essentially a documentary story. Even in the abridged theatre version, which contains fewer details than the detailed novel, it manages to convey a lot to the audience thanks to the actor’s existence not acting out the story as a play, but telling it. It is no coincidence that the Jantar Award-winning play also features a narrator character (Jan Monczka). In essence, it is a spectator’s tour through the pages of one city and its inhabitants, who have had to endure too much. But history, including the present day, teaches that “too much” is never too much.

Photo Courtesy of Těšínské Divadlo Theatre.

One of the key themes of the play is the fear of the fragility of the world in which one cannot feel safe. This is very acutely and emotionally perceived by the audience in the auditorium and therefore it is easy to identify with one or another character in the play. There is no distance of language, epoch, or history. Humanity here is in the timelessness and I think this fact was one of the key factors for the selectors of the MITEM program and its leader Attila Vidnyánszky. It is amazing how the spectator of the play, even if he or she is not familiar with the novel or the history of the Czech Republic and Poland, feels confident and does not get lost in the director’s idea or the twists and turns of the plot. Everything here is very precisely and smoothly structured and the play is perceived as a fascinating film with remarkable acting, laconic and restrained scenography and costumes (Marta Roszkopfová), and musical and sound accompaniment (Dorota Barová).

Humility, naivety, ardor, passion, love, bitterness of loss and suffocating misfortune, hope shattered by hopelessness – the palette of the two-and-a-half-hour performance is voluminous and contrasting. There is no pathos or techniques that solicit tears or laughter from the audience. But there are strong women, left without men, who are taken away by misfortune or war, but they are not broken and have not lost themselves. Everything here is very harmonious and moderate. At times, Our Town by Thornton Wilder comes to mind, but only because human perception is organized in such a way that it tries to latch on to what has already been seen, felt, and understood….

Photo Courtesy of Těšínské Divadlo Theatre

The church bell is ringing and no one will ask who it is ringing for. Curiously, even nowadays, the history of one town continues to grow with new details. In May 2021, the Gulag.cz team conducted research and discovered a hitherto unknown camp for Soviet prisoners of war in Karviná. Nearby were the remains of three other Nazi camps from the Second World War. Specialists were advised by Karin Lednická, the author of the novel that forms the basis of the play. However, these events are unknown to the characters in the play but known to the audience, who have the opportunity to imagine what awaits each character.

Photo Courtesy of Těšínské Divadlo Theatre.

Karin Lednická has performed a unique act of creation – her literary work has breathed life into an essentially destroyed city. A city that has experienced both booming prosperity and oblivion in the era of the booming prosperity of the idea of socialism. It is a lesson and a warning to posterity. It is a unique work on the theme of memory, like a flower breaking through the asphalt, overcoming prohibitions, silences, indifference and the desire to forget. The theatre continues this work by “bringing to life” the characters of the novel, who emerge from oblivion. This is not a distant past but it is somehow hidden from us. Without making sense of it, we risk repeating it over and over again. Memory work, source analysis, and immersion in context – this is what makes Leaning Church’s novel and performance an important theatrical and social experience that is worth living with the actors for everyone in the audience.

Photo Courtesy of Těšínské Divadlo Theatre.

MITEM continues to inspire audiences with its contrasting palette of theatrical experiences. It is a theatre not for entertainment but for the work of the mind and soul. It is demanding to itself and to the audience, which, leaving the performances, does not feel tired, but, on the contrary, feels the desire to talk, to share opinions and impressions. And it is this fact, and not only the long applause at the finale, that means that the festival achieves its goals, achieves the attention and understanding of the audience regardless of age, origin, language, faith and attitude to art… It means that the “church” of theatre is not leaning.

Photo from the official site of Těšínské divadlo theatre https://www.tdivadlo.cz/sztuka/krzywy-kosciol

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.