The Hoshruba Repertory Theatre Festival, which begins on September 12 at Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai, will celebrate the art form and the beauty of Urdu language

In 2011, while participating in the Faiz Ahmed Faiz festival in Lahore, theater personality Danish Husain was gifted a book of Urdu short stories written by Ali Akbar Natiq. After reading, Husain thought of working on a play based on those stories. Things progressed only after they met, and Ek Punjab yeh bhi premiered at Mumbai’s Prithvi Theatre Festival in 2015.

After changes in the cast, the play returns to open the Hoshruba Repertory Theatre Festival at the same venue with two shows on September 12. The six-day event will mark 11 years since Danish formed the Hoshruba Repertory Theater group. The schedule will include another play in Urdu and two in English, besides a Dastangoi (storytelling) session and a new production based on the life of poet-lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi.

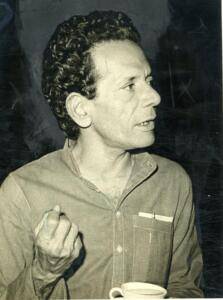

Danish Husain. | Photo Credit: Idris Ahmed

Asked whether he expects different audiences for the Urdu and English plays, Danish says, “In a place like Mumbai, or Delhi, a lot of us are polyglots, who follow and speak different languages. We watch both Hindi and English films, and in day-to-day practice, speak two or three languages. I would thus expect a similar audience for both.”

Polyglot audiences

Such polyglot audiences have become more common over the past two decades, which has also seen a revival in Urdu theater, with more younger audiences appreciating the art form. According to theater personality Salim Arif, one reason is the use of spoken language. “The language is dependent on the characters. Thus, one normally finds a mix of Urdu and Hindi, or Hindustani, which people relate to,” he says.

According to experts, Urdu theater has come a long way since it attained its identity in the mid-19th century, through musical dramas (rahas) during Wajid Ali Shah’s tenure. Agha Hasan Amanat’s Inder Sabha, staged in 1853, was an early success. Scholars cite the role of Parsi theater groups which staged farcical Urdu afterpieces after the main Gujarati play. There were also Urdu adaptations of William Shakespeare, most notably by Agha Hashar Kashmiri. That phase was followed by drama based on serious social and moral issues. Eminent writers like Imtiaz Ali Taj (who wrote Anarkali), Saadat Hasan Manto, Ali Sardar Jafri, Majnun Gorakhpuri, Upendra Nath Ashk, and Rajendra Singh Bedi contributed to theater literature.

Zohra Segal | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

In the 1940s, Prithviraj Kapoor’s Prithvi Theatres introduced actresses like the sisters Zohra Segal and Uzra Butt to the Urdu stage. The Indian Peoples Theatre Association (IPTA) performed plays and adaptations by Khwaja Ahmed Abbas, Ali Sardar Jafri, Ismat Chughtai, Ashk and Habib Tanvir.

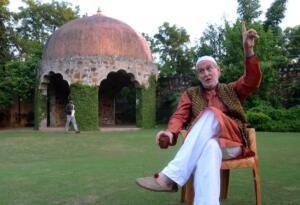

Habib Tanvir | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

In fact, September 1 marked the birth centenary of Habib, best known for Agra Bazaar and Shatranj Ke Mohre in Urdu, and later for using Chattisgarhi dialect. The Urdu adaptation of Girish Karnad’s Kannada play Tughlaq attracted those into historical subjects. Among women, Begum Qudsia Zaidi, Sheila Bhatia and Zahida Zaidi were also prominent.

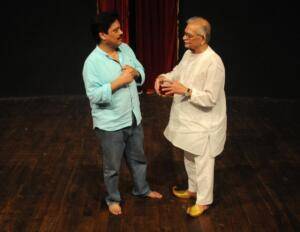

Director Salim Arif with Gulzar | Photo Credit: VIVEK BENDRE

Blend of Hindu and Urdu

Many later-day playwrights and directors used a blend of Hindi and Urdu. Says Salim, “The language commonly known as Hindustani was preferred, and writers like Javed Siddiqui and Gulzar excelled at that. Plays like Tumhari Amrita, Begum jaan and Ismat apa ke naam have aided the revival.”

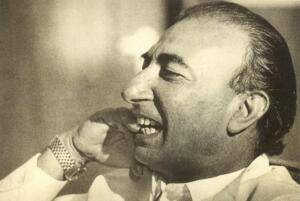

Tom Alter | Photo Credit: Sushil Kumar Verma

Actors Naseeruddin Shah, Farooq Shaikh, and Tom Alter also played a major role in popularizing Urdu theater. Says director M. Sayeed Alam of Pierrot’s Troupe, “Tom Alter was a genius. When I was looking for someone to play the title character in Maulana Azad, he was the best choice because besides being a fantastic actor, he was an authority on Urdu.”

Sayeed Alam’s play Ghalib | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

Some plays worked on a commercial level. According to Salim, Feroz Abbas Khan’s musical stage adaptation of Mughal-e-Azam has attracted the younger generation towards Urdu theater. Sayeed points out his hit comic play Ghalib In New Delhi, in which the poet is reborn in contemporary Delhi, has created awareness about classical poetry, even though many dialogues are in Hindi. Other forms like the ancient storytelling format Dastangoi witnessed a revival in the 21st century through Shamsur Rahman Farooqi, Mahmood Farooqi, Danish Husain, Syed Sahil Agha and Fouzia Dastango.

Theater directors are, of course, averse to simplifying the language just to cater to the masses. Says Danish Husain, “The language has its own charm, its own beauty. That must not be compromised. When we stage Shakespeare, we use the language as he wrote it. In my case, I try to create non-verbal cues through the sets and music. Ultimately, it’s the overall experience that matters.”

Shabana Azmi and Farooq Shaikh in Tumhari Amrita. | Photo Credit: Sampath Kumar GP

Despite the talk of revival, one major challenge is that many people still feel it’s a niche form. Explains Sayeed, “The truth is that Urdu theater is appreciated even by those who do not read and write Urdu. Yet, a lot of plays are targeted at the Urdu-wallahs. There should be more efforts to take it outside to the non-Urdu-centric audiences.” According to Danish, another challenge is the existence of too many alternatives. “We live in a very visually and informationally overloaded society that it becomes difficult to reach out to new audiences,” he says.

The good news, of course, is that good plays always attract audiences and have multiple re-runs. It’s a world driven more by skill than by stardom.

The curtains go up

A highlight of the Hoshruba Repertory Theatre Festival to be held at Mumbai’s Prithvi Theatre from September 12 to 17 will be the premiere of Main pal do pal ka shayar hoon, a dramatic storytelling of the life of poet-lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi. Directed by Danish Husain, it was initiated through an idea mooted by Amita Talwar of Hyderabad-based Art For Causes, and written for the stage by Mir Ali Husain and Himanshu Bajpai.

There will be two performances featuring Danish Husain and Vrinda Vaid “Hayat” on September 17. Live music and poetry recitation will be part of the set-up. Says the director, “What made Sahir first among equals was not just his ability to bring the fire of truth to his words, but his uncanny ability to sense the pain of the masses and his skill to present profound ideas in simple words.” Adds Amita, “I have been wanting to do a series on various poet-lyricists for a long time, after doing a documentary on Kaifi Azmi in 1999. I approached Mir Ali Husain to work on a theatrical presentation on Sahir saab, and when we met Danish, everything fell in place. After Prithvi, we plan to stage it in Hyderabad, where I am based.”

Hoshruba Repertory was formed in 2012 by Danish Husain with the intention of bringing literary texts alive on stage. Settled in Delhi, he left a career in banking to focus on theater. He specialized in Dastangoi, a format of storytelling, and his multilingual series Qissebaazi was much appreciated. Eventually, he wanted to play different characters, and as a director, made plays both in Urdu and English.

The festival will feature a play on Sahir Ludhianvi | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

The festival will begin with two Urdu plays — Ek Punjab Yeh Bhi, based on the short stories of Ali Akbar Natiq and Qissa Urdu Ki Aakhri Kitaab Ka, an adaptation of a satirical text by Pakistani poet and humorist Ibn-e-Insha. The latter will feature Yasir Iftikhar Khan and Husain. Chinese Coffee, an English play written by Ira Lewis, and featuring Vrajesh Hirjee and Danish will be staged on September 14. Hirjee also acts along with Joy Fernandes in the following day’s play Guards At The Taj, written by Rajiv Joseph . The festival will also have the Dastangoi feature Qissebaazi, containing an excerpt from Tilism-e-Hoshruba by Syed Muhammad Hussain Jah, before concluding with the play on Sahir Ludhiavi presentation.

According to Danish Husain, Tilism-e-Hoshruba is one of the grandest fantasies ever written. “There will be stories within stories, and inter-temporal and inter-spatial leaps which you never expected,” he promises. Both Qissebaazi and the Sahir-themed event should be a treat for theater enthusiasts.

This article was originally published by The Hindu (https://www.thehindu.com/). Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Narenda Kusnur.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.