Susanne Kennedy doesn’t do things by half. When she creates a world, it has its own logic, its own rules, its own ethos. It’s not a world of participation but one where the audience are invited to watch but always slightly distanced from the stage action. Here working with visual artist Markus Selg — both share responsibility for the concept, she directs and he designs — she creates a new piece, touring since last summer, centring on the rituals and routines of a social influencer, Angela, who creates videos to post on YouTube. She films herself repeatedly – perhaps one of the strange (or not so strange) loops of the piece’s title. There is no real excitement, no crisis, no narrative as such. The action is banal as Angela goes about her daily routines — a loop of sorts that mutates into a different loop as she is diagnosed with a undefined autoimmune condition, never specifically named but one causing a clear physical disintegration in Angela’s health through the duration of the piece.

The action (in as far as there is “action” in the conventional sense of the term) sees Angela visited by her boyfriend Brad, her friend Susie and her mother. They come and go — entering through one door and leaving out of another, defying the logic of causality — as she gets sicker and sicker. Angela remains suspended in a state of decay, the loop of the play’s title where the audience are invited to reflect on humanity, automation, and repetition. Angela never leaves her room; her room is her world but this world also seems to resemble a TV studio, where nothing feels real and where the real is in and of itself called into account.

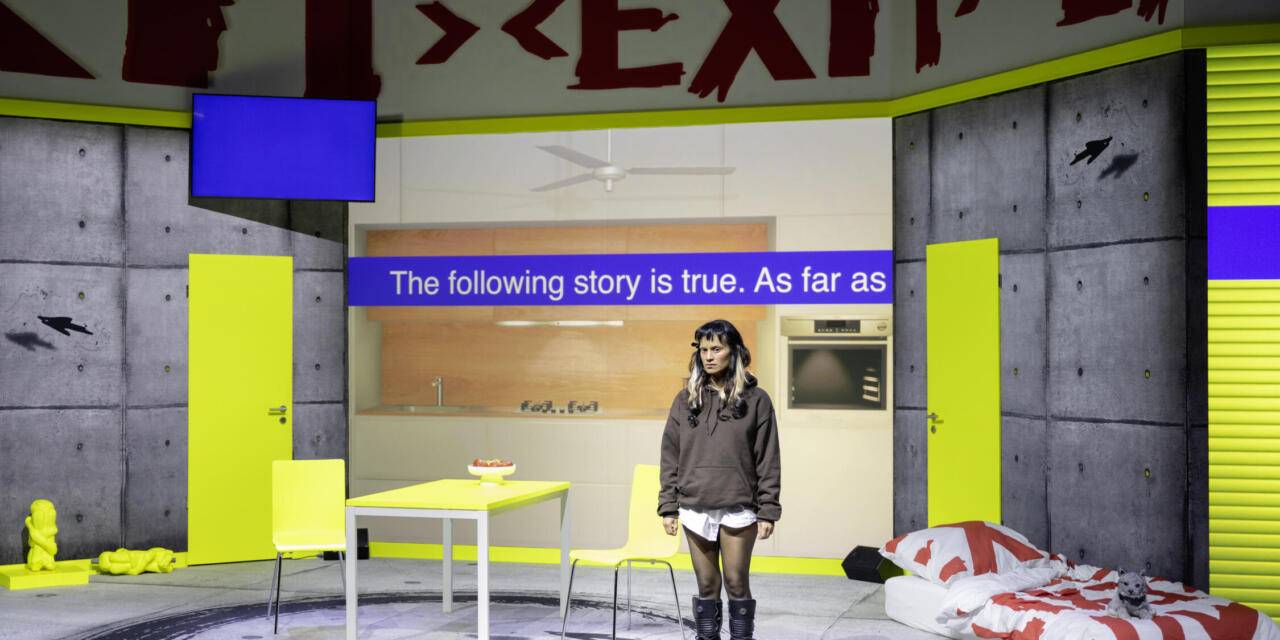

The piece gives very little information on what Angela thinks: motivation is non-existent, exposition minimal. Her transformation is realised through changes of movement, the body increasingly disconnected from the demands the mind makes of it. The room has a strangeness about it that matches Angela’s strangeness; its design has more in common with a video game than a proscenium arch design with its projections and lettering. EXIT features prominently on a banner at the top of the room. Angela’s rumpled bed remains stage left. Fluorescent lime green doors match the minimalist table and chairs. It looks like a showroom rather than a lived environment. Screens show Angela’s soft toy — a strange bear-cum-cat that speaks — and a series of messages projected that alert an audience to the piece’s structure in three parts. But as with much in Kennedy’s theatre, this not a message that can be taken literally. The projections give announcements that should not always be believed. The following story is true as as far as I know, the captions inform the audience, but what is truth in a post-human world? Whose truth are we subject to? Who is defining truth? Information overload is often a feature of the piece. How do we navigate our way through it?

Observe closely and it’s clear the actors are lip-synching, sound coming from elsewhere rather than their mouths; it’s precise, technically impressive but not real. In effect, it creates from the very opening the illusion of the real that is pulled apart through the strangeness of the action (or rather inaction) of the characters. The non-alignment remains a constant reminder that this is theatre and not life; that these are actors very consciously performing with technological enhancement. Brad bites into an apple on the kitchen table and says it’s not real but it looks real and, on another occasion, it is eaten, pointing to the fact that it is real. But who defines the real in an environment where nothing is quite what it first appears? Beyond the surface there is no deeper reality, there are just layers, as in Peer Gynt, endlessly peeled away to reveal more and more layers. Angela’s life may be a sequence with no end — beyond that imposed by the end of the performance — and no logic.

A whirring soundtrack creates a sense of unease — Richard Alexander’s sound design is never less than multilayered. Sounds are magnified, as with the character’s eating. Angela’s mother might be the same age as her, breaking down the idea of mimesis in characterisation. Her mother coughs up a baby – a process of giving birth that provides something of the cradle to grave narrative – albeit dismantled and reconfigured in a decidedly unrealist manner.

At the end Angela remains a mystery – there are no answers, no reasons, no closure. The action becomes stranger as dreams filter into the set and take it over: Angela’s imagination is livelier and more animated than her deteriorating body. A punk guardian angel — a choral figure of sorts — converses with Angela. As Angela’s condition worsens, the stage becomes a more feverish space. Colours and sounds intrude to rupture the cool order evident at the production’s opening.

The order falls part in Susanne Kennedy and Markus Selg’s ANGELA (a strange loop). Photo Julian Röder.

Seen at Madrid’s Teatros del Canal, I missed some of the intimacy that a smaller space might have offered in the sense of an audience member feeling they were observing Angela’s journey as if in an art gallery. Kennedy creates something of the coolness of an installation, an art piece where everything has a place and a look. Watching in a large auditorium, I perhaps felt too distant from the action in the way that I never do in a video game where the illusion is there of being very much part of the immersive world. This may be exactly what Kennedy wants and there is no doubt that the strangeness of the encounter creates an unsettling experience. ANGELA (a strange loop) asks questions of theatre and its purpose that are never less than intriguing. It provides a different model of acting — the cast, Diamanda La Berge Dramm, Ixchel Mendoza Hernández, Kate Strong, Tarren Johnson, and Dominic Santia perform as if on autopilot with a rigidity of gesture and tone that feels appropriately robotic. ANGELA (a strange loop) operates as an intriguing intellectual exercise in theatrical play where disengagement feels the name of the game and our perceptions and expectations are consistently questioned.

ANGELA (a strange loop) opened in the summer of 2023; it played at the Teatros del Canal Madrid on 8 and 9 March 2024 and continues touring.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.