Introduction by Michael Schweikardt

Student designers at San Francisco State University’s School of Theatre & Dance spent several months preparing for their upcoming production of Sarah Ruhl’s 2003 play Eurydice. The semester-long pre-production required the student scenic designer, student costume designer, student lighting designer, student sound designer, and student prop designer to enroll in a class called TH A 740 Play Production Concepts.[1]All SF State BA Theatre Studies students who are chosen to design a production enroll in this class and receive a letter grade and three units for their labor. They met for two-hour sessions, once a week, for fifteen weeks to collaborate with one another, their faculty director, and design mentors.[2]Professor Bruce Avery is directing the production. Emeritus Professor Joan Arhelger mentors lighting designers, Lecturer Cliff Caruthers mentors sound designers, Professor Todd Roehrman mentors … Continue reading

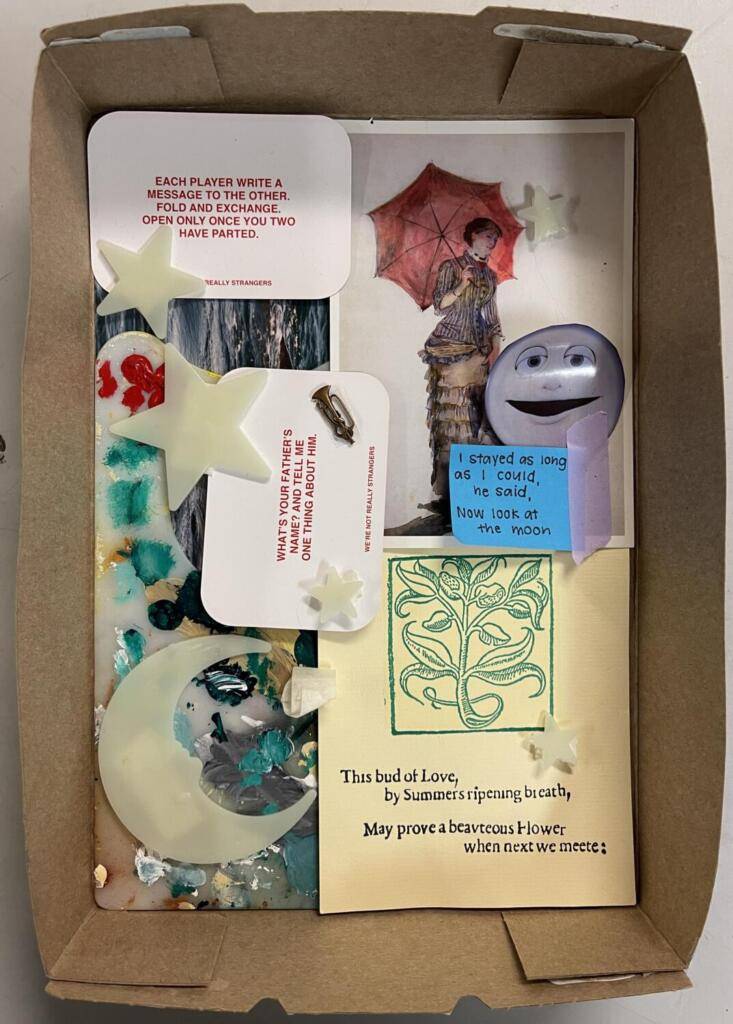

Along the way, the designers engaged in Given Circumstance Script Analysis. They read dramaturg Elinor Fuchs’ 2004 essay Visit to a Small Planet and created mood boards and Joseph Cornell-style boxes in response.[3]Although not overtly an essay about play analysis for designers, Elinor Fuchs’s 2004 essay “EF’s Visit to a Small Planet: Some Questions to Ask a Play” offers a refreshing alternative to … Continue reading They read set and costume designer David Zinn’s Some Advice for Graduating Designers and, following his advice, articulated their own personal libraries.[4]In his 2020 essay “Some Advice for Graduating Designers”, set and costume designer David Zinn refers to the “library in [your] own head – the interests and obsessions that answer the … Continue reading They read stage designer and scholar Richard M. Isackes’ 2008 essay On the Pedagogy of Theatre Stage Design: A Critique of Practice and answered his questions, “what will be your entry point into this project” and “how do you personally connect with the world of the play” (43)? They made preliminary designs, and refined their ideas in the form of models, renderings, light plots, etc., all leading up to a culminating event known as the “Design Reveal”, where they shared their proposed designs with faculty, staff, and other students. But first, I asked the designers to pause for reflection. I prompted them to look back on their own process and clarify (for themselves and others) how they arrived at their design, what they are trying to achieve, and why – and I asked them to write it down.

Scenic Designer Jessa Laboissonniere meditates on the role of grief in Eurydice while processing her own loss and concludes that experiences of grief are unique and highly personal. The visual language she chooses to express grief in the scenic design becomes a conversation, not a conclusion. Lighting Designer Tristan Fabiunke begins his work by responding to the structure of Sarah Ruhl’s text as three distinct movements. He explores the movements of the play as separate but related worlds and discovers room for vivid color in the realm of the dead. Costume Designer Bre Lawscha looks at the play thematically and identifies memory, timelessness, and family as three organizing principles through which to view the world of Eurydice. As Sound Designer Connor Diaz wrestles with the surrealist tone of the play, he comes to understand the need to represent the tension between the uncanny and the nostalgic by allowing them to coexist in the soundscape. And Props Designer Benjamin Zingos connects the aura of objects with their ability to stir memories, however fleeting, in all of us.

What emerges is a snapshot of how five designers, working in concert to realize a production, articulate their uniquely personal responses to the same theatrical text. Moreover, the work of these designers (the work of all theatrical designers), is ephemeral; it will exist briefly and then be gone. This short, co-authored collection of essays serves as a record of a process and documents the thoughts and concerns of young theatrical minds.

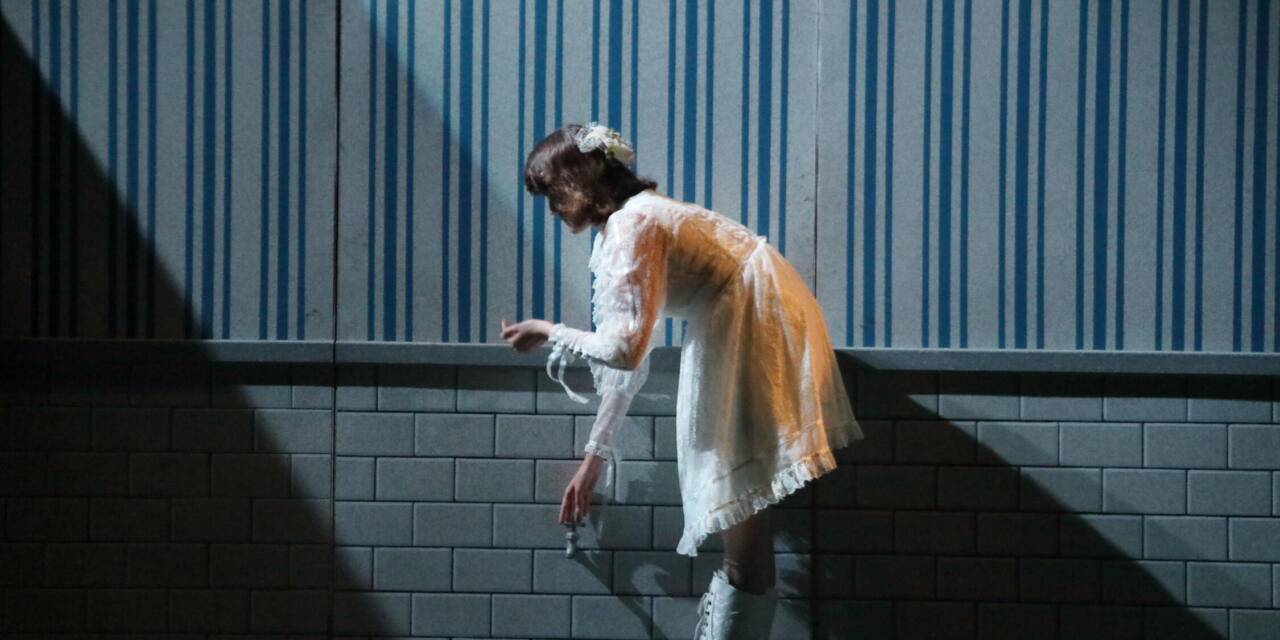

Eurydice Scenic Design by Jessa Laboissonniere

Eventually something you love is going to be taken away. And then you will fall to the floor crying . . . you’re falling to the floor crying thinking ‘I am falling to the floor crying’ but there’s an element of the ridiculous to it – you knew it would happen, and even worse, while you’re on the floor crying you look at the place where the wall meets the floor and realize you didn’t paint it very well. – Richard Siken, Poet, from an interview with James Hall.

I find myself relating deeply to Sarah Ruhl. She wrote Eurydice in memory of her father, who passed away from cancer when she was 20, and I first read it under near identical circumstances. I read every word which she has published about the play with careful examination. I ruminate on Eurydice’s captivating imagery and find it to be so poignant and personal to her life that I cannot help but be moved by her painting of grief. Ruhl expressed in an interview for The Metropolitan Opera that though Eurydice is not entirely autobiographical, “it’s like taking significant fragments of your life and placing them within, or pushing them through, a giant myth that is much bigger than yourself” (Schelling).

Similarly, scenic and costume designer David Zinn advises designers not to “talk about what the play is about but rather . . . what does it push against” (Zinn). Eurydice pushes against the mythology of Orpheus and Eurydice’s story, and in turn my design for Ruhl’s world pushes against not only the play, but the mythos of grief.

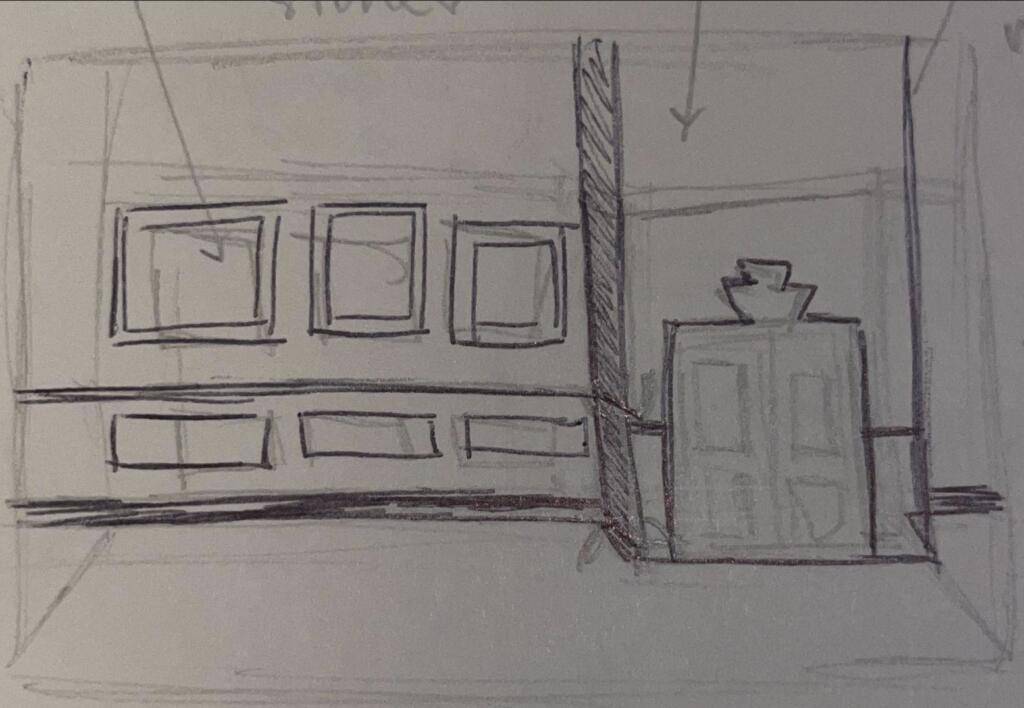

Scenic designer Jessa Laboissonniere’s thumbnail sketch of an early design idea for Eurydice.

Grief, writer Margaret Renkl observes, is a conversation. She says that “everyone [she has] ever loved is gathered around the same table, talking” (Renkl). In my design for Eurydice, I find myself sitting at my own table, talking to my own loved ones, my collaborators, and Sarah Ruhl. This table is too large and amorphous to form itself in a way which speaks to any one presentation of what grief feels or looks like. To welcome an audience into the world of Eurydice, the visual language of the scenery must be a language that everyone speaks. Margaret Renkl’s understanding of grief as a conversation became the jumping off point for creating a visual language in which the design converses with Ruhl’s script.

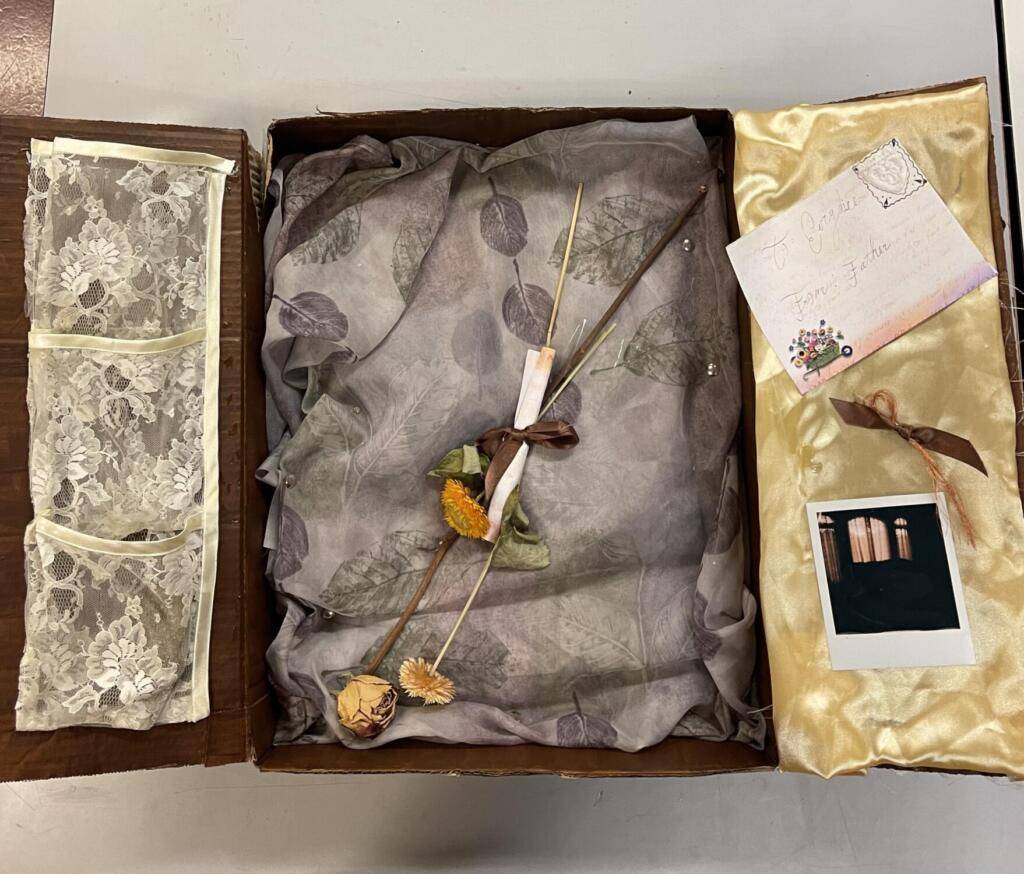

Scenic designer Jessa Laboissonniere’s Joseph Cornell-style box for Eurydice.

The vocabulary of my design for Eurydice is geometric and abstract. I drew heavy inspiration from a wide library of sources: from Georgia O’Keeffe’s “The Beyond” to video games such as Nomada Studio’s GRIS.[5]Georgia O’Keeffe’s “The Beyond” is a highly abstract landscape from 1972. The bottom half of the painting depicts a horizontal band of black below a band of blue (suggestive of sky) … Continue reading From these sources I derived six monolithic flats, decorated with 1950s pinstripe wallpaper and subway tile (inspired by San Francisco’s Forest Hill Station). The monoliths move and reconfigure themselves into the ever-malleable, ever-changing Underworld. They become the words of the conversation that is Eurydice.

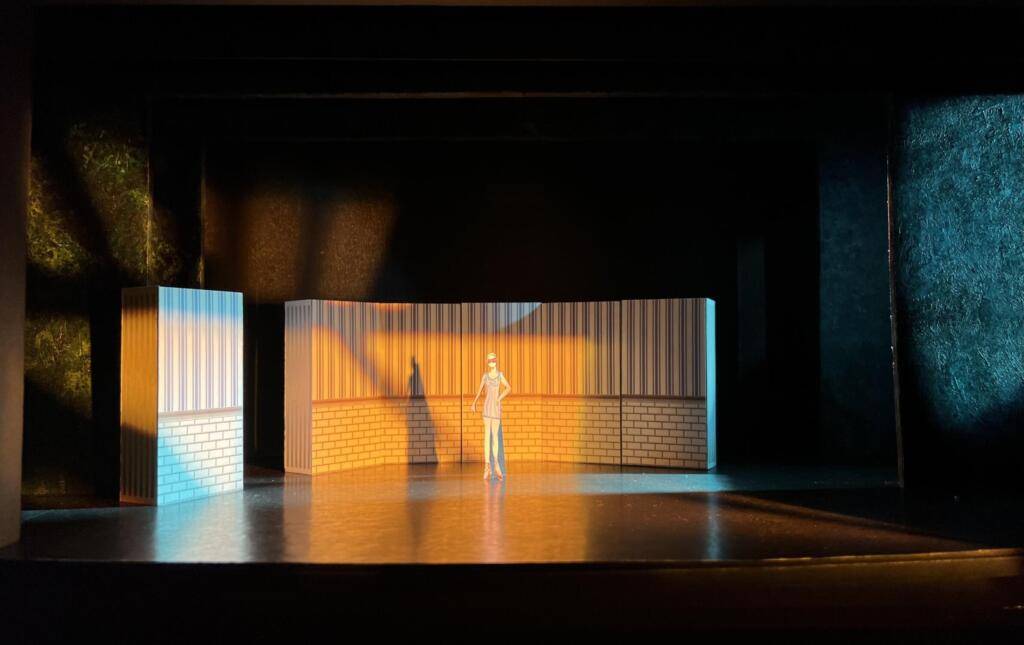

Scale model of scenic designer Jessa Laboissonniere’s design for Eurydice.

Upstage of the monoliths is a scrim which allows us to simultaneously view the Overworld and the Underworld. Curt Columbus, the artistic director for Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, Rhode Island, notes that Ruhl’s plays “limn the space between life and death” (Goodman). The use of a scrim allows our production to do just that.

The dual presentation of life and death is contained by two false-proscenium-portals, pushing the playing space inward and furthering the physical overlap of the Earth and Hades. This allows them to coexist and interplay with one another, which furthers Ruhl’s interpretation of the Underworld as not that far and not that inaccessible by those on the upside.

My interpretation of Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice is a conversation. It hopes to bridge the deeply personal script of Ruhl with the universal experience of grief through a visual language anyone can speak.

Eurydice Lighting Design by Tristan Fabiunke

When I first read Eurydice, I noticed a defining aspect of the play’s structure: the three movements that serve to divide the play into three parts. These movements shift the play in time, place, and tone, and I began to think about how I could underscore each movement with differences in lighting to enhance the dramaturgy of each part and make them feel unique.

A rendering of the “golden hour” by lighting designer Tristan Fabiunke with Midjourney.

The first movement is heavily focused on Eurydice’s and Orpheus’s fleeting time together in the living world. To underscore the short time they experience their perfect romance, it seemed fitting to place the whole movement under a sunset, giving the audience the subliminal message that everything happens in just those few perfect moments right at the “golden hour.” In the second movement, after Eurydice’s death, life seems to vanish out of the living world, and Orpheus becomes washed in a greyscale made of monochromatic blues. As the living world loses its life, the Underworld becomes the focus of the play, and becomes more alive than its counterpart. I knew I would need something unique and vivid to enhance the strangeness and importance of the Underworld, so I decided to produce the complete visual opposite of the living world in this movement. Instead of greyscale, like film noir, the Underworld would be defined as “neo-noir” which uses bright, vibrant colors and gorgeous contrast to make a stunningly dramatic image. For the last movement, the environment becomes defined by the presence of the “gates of hell” as Orpheus tries to take back Eurydice. To make this apparent I want to recreate the size and impact of the door using grand strips of light spilling out from under the door and through the crack as it opens slightly ajar.

Lighting designer Tristan Fabiunke lights the scenic model for Eurydice in a “neo-noir” style.

To tie it all together, we recently stumbled upon a style that serves as a through line for all our ideas: geometric abstraction. Large hard lines and edges define one space from another, so a lot of my design will be underpinned by geometric motifs. I hope to use grand, sweeping cuts of light which dramatically define spaces and will create excellent contrast between the environment and the performers.

Lighting designer Tristan Fabiunke explores geometric abstraction in lighting the scenic model for Eurydice.

Eurydice Costume Design by Bre Lawscha

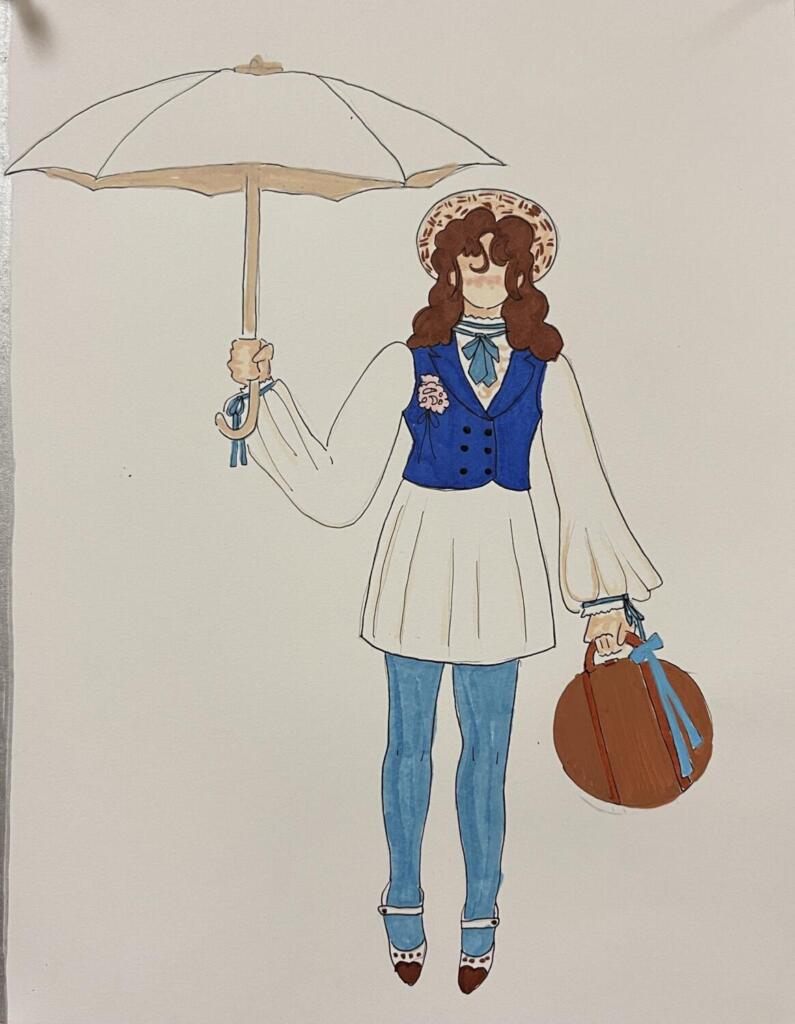

Eurydice by Sarah Ruhl puts a twist on the Classical Greek myth of Orpheus by focusing on Eurydice’s side of the story. The main themes of the play are death, and how loved ones handle their grief.

Memory: Something that connects us all is memory – memories of those who have passed. In my own personal life, I have not experienced the great loss of a loved one, but I have witnessed my parents and close friends experience the grief of losing someone they love. At the beginning of the design process for Eurydice the design team was tasked with creating a Joseph-Cornell-style-box inspired by the play. I created a memory box that might have belonged to Eurydice’s grandmother when she was alive, and I filled it with mementos connecting to each of the characters in the play. This became the starting point for my costume designs. I want audiences to see themselves and their loved ones in these characters. In life and death, we remain connected to our loved ones.

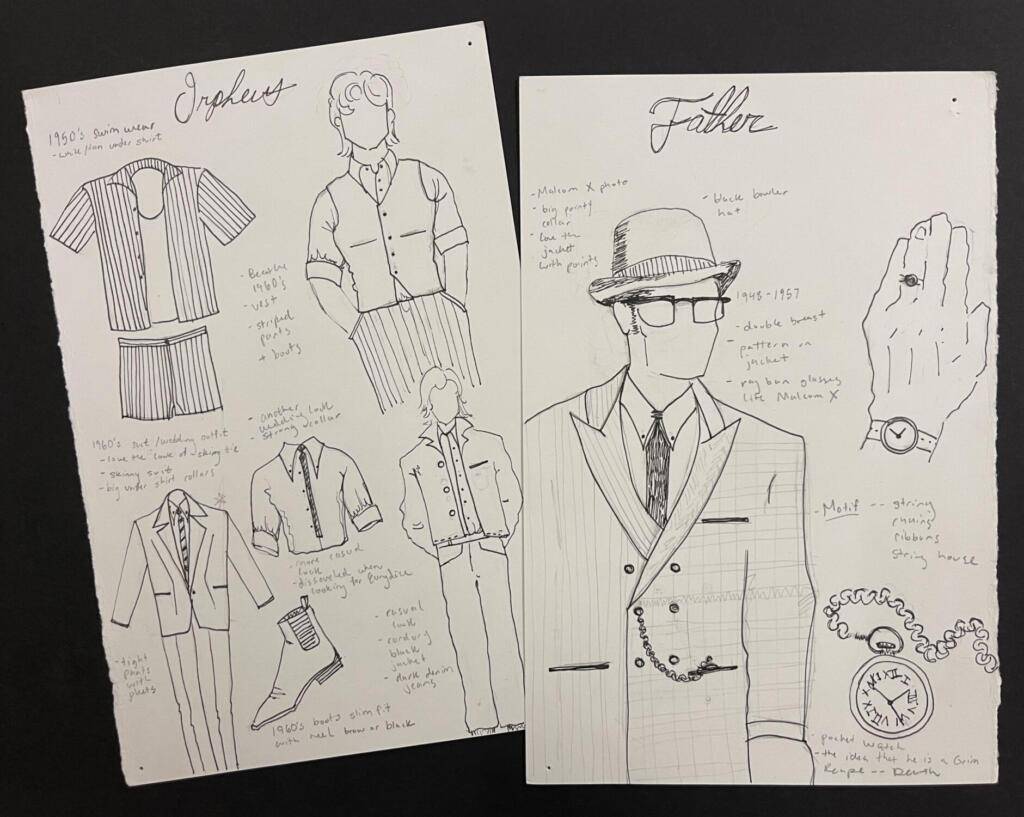

Timelessness: Thanksgiving dinner, a house made of string, Grandmother’s piano, hotel staff, heightened language, Eurydice takes place in another dimension. There is no set place or time – yet it is familiar; a place and time the audience can connect to. There are two specific time periods mentioned in the script: (1) the 1950s expressed in Eurydice’s swimsuit and, (2) the 1930s expressed in Eurydice’s wedding suit. This story is not Classical (in the Ancient Greek sense). Instead, I am giving each character their own style and individual history for the clothing they wear.

Costume Designer Bre Lawscha’s thumbnail sketches of early ideas for Eurydice.

In the script, Eurydice’s character is referred to as “interesting.” How is our main character interesting? What makes her interesting for the dimension she inhabits? To answer this question, I researched youth-countercultural-fashions from different periods and used them to inspire Eurydice’s costumes. I want to stray away from classical beauty and create an “interesting” quirkiness for Eurydice.

Family: I imagine all the characters in Eurydice connected by a giant family tree. Eurydice’s father symbolizes death as a gentle spirit, coming to greet Eurydice at the entrance of the Underworld. The Stones are Eurydice’s guardian angels, family members from past generations who had their own lives. When Eurydice dies, they are also at the entrance of the Underworld to greet her. Then, they transform into “hotel staff” who serve her. The Interesting Man, lord of the Underworld, owns the hotel and is the boss of The Stones.

Here is a list of phrases I developed to guide my design thinking:

Another dimension

No set time period

Not Classical

The audience sees themselves and their own stories

Each character has a story and a connection with one another; tie everyone together

Family; family tree

Past life

Hidden story–design

Clothing tells its own story without words

A combination of classical designs from different time periods

“Interesting”; what is interesting?

Counterculture

Color theory / color scheme

Establish connections through color

The afterlife is colorful

A memory box started my journey

What do people leave behind?

Clothing as history; Clothing as past life

Eurydice Sound Design by Connor Diaz

My process for imagining the sounds and melodies in Eurydice started by looking at the surrealism present in the play. The story grounds itself in the ideas of tangible memory in the form of letters, literature, and music, but the nature of the Underworld is to eliminate attachments to that plane of reality. It is this ongoing conflict in Eurydice that helped inspire the sounds one may hear throughout this production.

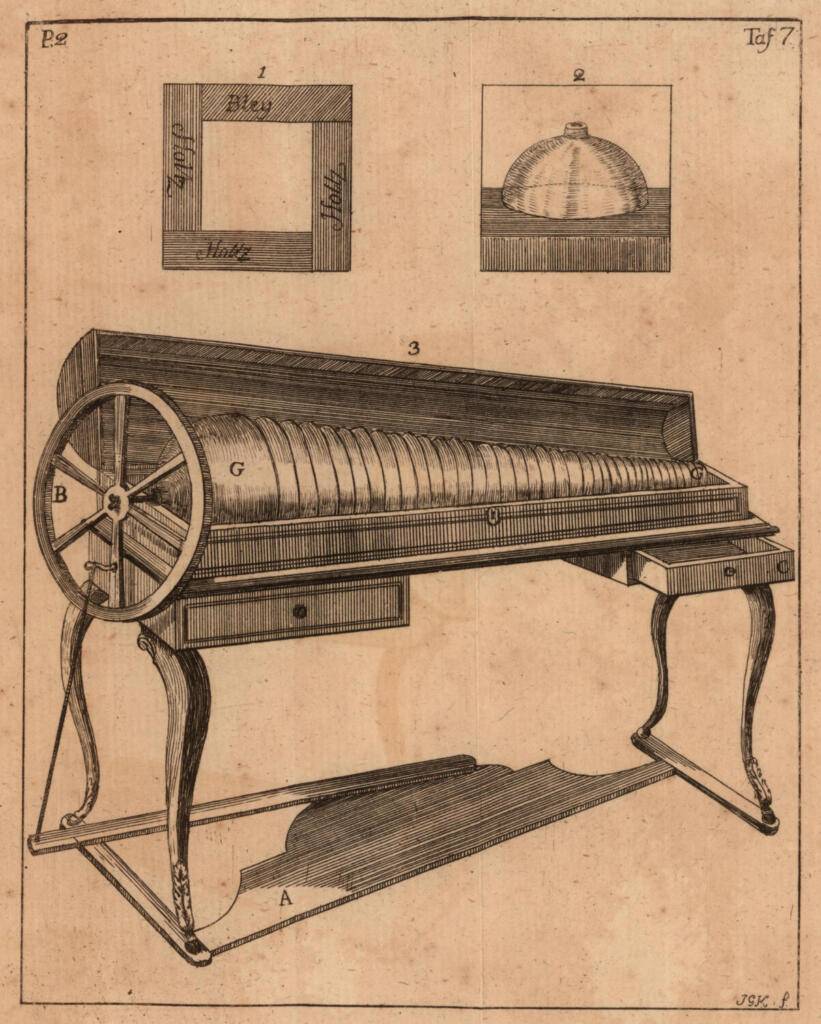

At first, I considered each character individually and started looking for musical motifs that would thematically represent the personalities and motives of each character. My first vision for the show was to have the character of Eurydice be represented by more contemporary piano pieces in contrast to her father’s piano pieces which would harken back to the sounds of old jazz standards from the 1920s. I was fascinated with the idea of having the non-diegetic sound of music (music that is heard by the audience but not the characters) played over a phonograph for the effect that vinyl has on a piece of music. I hope this will create a level of detachment from any particular moment in time and create a sense of timelessness. For the character of Nasty Man, I considered a saxophone because of the playfulness it can evoke from the audience, and the hypnotic effect it might have on Eurydice. The Stones I imagined as both percussive and woodwind instruments. When I was imagining the language of the stones, I envisioned a hollow sound, like wind whistling through mountain passes, devoid of life but still full of will. I also envisioned the characters being highly active on stage so I felt that rhythmic clicking sound would be an interesting way of representing the playfulness of their characters. Finally, Orpheus’ motif was clearly gravitating toward some sort of string instrument since it hints at that in the text. But I thought that would be too easy. What if, instead, Orpheus was devoid of any strings to work with?

I want the soundscape of the piece to feature instruments that are unconventional, such as the glass harmonica (an instrument that is from the 1700’s and involves the use of glass bowls aligned on a pole to create haunting melodies), and theremin (another instrument that is operated in an unorthodox way by moving one’s hands in a negative space to effect the waveforms created by the instrument). The theremin intrigues me because of its almost haunting sound, like some distant and alien wail, or even perhaps a stringed instrument much like the one Orpheus longs to find in Eurydice. We had many discussions about balancing those unusual melodies with more familiar pieces that are not necessarily recognizable to the common listener, but still evoke the same comfort that one feels at home.

A drawing of a glass harmonica.

Thematically, the struggle between memory and the all-encompassing void that death provides is a constant throughout the show. Once I came to that realization, I understood that it was my job to create an atmosphere that rides the razor’s edge between nostalgia, comfort, and memory, and the discomfort provided by the unknown or uncanny. When viewed through that lens, my task became much more focused. I searched for different ways to elicit both feelings in separate pieces, however, I felt that the presence of the two moods in a single piece tended to grab me more as a listener. The contrast between the two ideas was so palpable in those pieces that it was hard to imagine them without the elements that make them both unsettling and charming at the same time – much like the story of Eurydice itself.

Eurydice Props Design by Benjamin Zingos

As I read Eurydice, I found myself ruminating on the Japanese concept of mono no aware (物の哀れ), which translates to “the pathos of things”. More specifically, this concept represents the understanding of the transience and ephemerality of life and reality, and the ability to appreciate its bittersweet beauty. I have been thinking a lot about how this concept relates to memory, and how objects can often bring an echo of a memory that has vanished back to life, only to be washed away once again by the passing of time.

The Interesting Man’s tricycle.

This inspired me to look at the various (sometimes bizarre) objects referenced in the script as objects present in memories that have lost their context or are incomplete. It also made me question how I could show the way time slips away from us through some of the props. One example of this is the glow-in-the-dark globe, which appears in the scene where Orpheus is trying to locate Eurydice on the telephone. I have an idea to create a globe that slowly turns from a standard globe in daylight to a glowing celestial map once the sun is set. In coordination with lighting, this might create the effect of a day slipping through Orpheus’ fingers as he tirelessly searches for Eurydice.

Michael Schweikardt enjoys a successful career as a set designer working for opera and theatre companies across the United States and abroad. He is Assistant Professor at San Francisco State University, School of Theatre & Dance. Essays in Teaching Critical Performance Theory in Today’s Theatre Classroom, Studio, and Communities (Routledge 2020); Text and Presentation, 2019 (McFarland 2020); Performing Ethos, (Vol. 10); and Teaching Performance Practices in Remote and Hybrid Spaces (Routledge 2022), demonstrate his research focus on the tension between materiality and ephemeral performances. He serves as managing editor for design at The Theatre Times and is co-editor of Prompt: A Journal of Theatre Theory, Practice, and Teaching. His work can be viewed on his website: www.msportfolio.com.

Connor Diaz is an artist from the Bay Area who has been involved in multiple productions at San Francisco State University. Credits include Water by the Spoonful, Marisol, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Rent. He is working on his BA in Theater Arts with an emphasis on performance. This will be his first time working on sound design and he is excited to create an atmosphere that complements the work of the actors and other designers of Eurydice.

Tristan Fabiunke is a rising fourth-year student at San Francisco State University majoring in technical theater and lighting design. He has worked in the Bay Area as an electrician, assistant lighting designer, and lighting designer. Some of his recent credits include assistant lighting designer for A Chorus Line (San Francisco Playhouse); lighting archivist on Goddess (Berkeley Repertory); and lighting assistant at Williamstown Theatre Festival (2022). SF State credits include lighting designer for University Dance Theater, assistant lighting designer and programmer for Rent, and assistant production manager and lighting designer for LCA (School of Liberal & Creative Arts) and LCA Live.

Jessa Laboissonniere is a rising fourth-year student at San Francisco State University pursuing a double major in Theatre Arts with an emphasis in scenic design, and Visual Communication Design. SF State scenic design credits include Doubt (2022), Rent (2023), and the upcoming Fall 2023 production of Eurydice. With a foundation in design principles and a love for visual storytelling, Jessa hopes her work engages audiences and enhances stories seen on stage.

Bre Lawscha is a rising fourth-year student at San Francisco State University, School of Theatre & Dance, pursuing a BA in Theater Arts with a focus on costume design. Bre holds an associate degree in Theater Arts from American River Community College. At SF State, Bre has served on several wardrobe crews, and was assistant costume designer for Rent (2023). Bre is excited to continue their design journey and to learn more about their craft.

Benjamin Zingos is a fourth-year student at San Francisco State University working towards a B.A. in Theatre Arts with an emphasis on performance. In Fall 2023, he will return to SF State to pursue an MA in Theatre Arts with an emphasis on directing. Eurydice marks Benjamin’s first production working as a designer. He is excited to broaden his understanding of the work of designers before directing his thesis project in 2024.

Works Cited

Fuchs, Elinor. “EF’s Visit to a Small Planet: Some Questions to Ask a Play”. Theater, vol. 34, no. 2, 2004, pp. 4-9.

Games for Change. Games For Change – Games – GRIS, 2023, https://www.gamesforchange.org/games/gris-2/. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Goodman, Lawrence. “Playwright Laureate of Grief.” Brown Alumni Magazine, 20 March 2007, https://www.brownalumnimagazine.com/articles/2007-03-20/playwright-laureate-of-grief. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Isackes, Richard M. “On the Pedagogy of Theatre Stage Design: A Critique of Practice.” Theatre Topics, vol. 18 no. 1, 2008, p. 41-53. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/tt.0.0005.

Renkl, Margaret. “More and More, I Talk to the Dead.” The New York Times, 30 January 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/30/opinion/death-grief-memory.html. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Schelling, Kamala. 2021. “A Conversation with Sarah Ruhl.” The Metropolitan Opera, December 2021. https://www.metopera.org/discover/education/educator-guides/eurydice/a-conversation-with-sarah-ruhl/.

Zinn, David. 2020. “Some Advice for Graduating Designers.” Three Views, May 2020. https://3viewstheater.com/david-zinn.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Schweikardt, Connor Diaz, Tristan Fabiunke, Jessa Laboissonniere, Bre Lawscha, Benjamin Zingos.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

Notes

| ↑1 | All SF State BA Theatre Studies students who are chosen to design a production enroll in this class and receive a letter grade and three units for their labor. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Professor Bruce Avery is directing the production. Emeritus Professor Joan Arhelger mentors lighting designers, Lecturer Cliff Caruthers mentors sound designers, Professor Todd Roehrman mentors costume designers, Assistant Professor Michael Schweikardt mentors scenic and props designers. |

| ↑3 | Although not overtly an essay about play analysis for designers, Elinor Fuchs’s 2004 essay “EF’s Visit to a Small Planet: Some Questions to Ask a Play” offers a refreshing alternative to given-circumstance-based script analysis. She suggests that “a play is not a flat work of literature, not a description in poetry of another world, but is in itself another world passing before you in time and space” (Fuchs). Fuchs instructs students to visualize the world as a planet by molding it into a ball and setting it at a distance. Then she advises them to ask the planet questions. For example: what is space like on your planet; how does time behave on your planet; what is the mood on your planet; in what kinds of patterns do the figures on this planet arrange themselves; who has the power on this planet? Next, I introduce students to the work of American artist Joseph Cornell, a pioneer in the art of Assemblage – the curation and arrangement of objects on and projecting out from a defined substrate or container. In Cornell’s case, he created miniature worlds by assembling found objects within containers, or “boxes”. What do Cornell Boxes have to do with Elinor Fuchs’s essay “Visit to a Small Planet”? They are their own planet; you can view them from a distance; they have their own rules, destiny, climate, mood, music; they have defined boundaries, containers; they tell a story. The Cornell Box expresses a total world. |

| ↑4 | In his 2020 essay “Some Advice for Graduating Designers”, set and costume designer David Zinn refers to the “library in [your] own head – the interests and obsessions that answer the ever-evolving question of who you are” (Zinn). Items that Zinn identifies in his library include: The Cockettes, Lynn Cohen’s photographs, Terence Davies’ movies, Nakhane, Shamir, Fleetwood Mac, Wozzeck, and more. The library in your head, or your personal library, is a unique and ever-changing catalog of interests, obsessions, and experiences that are particular to you. It expresses who you are and what you might bring to a play. Armed with this library, a theatrical designer might connect their personal narratives and interests to stories that differ from their own lived experiences. |

| ↑5 | Georgia O’Keeffe’s “The Beyond” is a highly abstract landscape from 1972. The bottom half of the painting depicts a horizontal band of black below a band of blue (suggestive of sky) interrupted by thin ribbons of white and gray. The overall effect is geometric and placid. Nomada Studio’s GRIS is a platform-adventure game released in December 2018. The website Games for Change describes it this way: “Gris is a hopeful young girl lost in her own world, dealing with a painful experience in her life. Her journey through sorrow is manifested in her dress, which grants new abilities to better navigate her faded reality. Gris will grow emotionally and see her world in a different way. GRIS is a serene and evocative experience, free of danger, frustration, or death” (Games). |