In 2004, Ireland, as one of the first countries in the EU, invited Polish people to live and work here. Over the past two decades, Poles have become the largest minority in Ireland, the Polish language is the second most-spoken language, Irish families attend many Polish weddings, Polish-Irish families are now a thing, many young Poles speak Polish with Irish accents, and many Irish speak Polish at home. With this, new ways of understanding Ireland, its culture, its people, and the world have emerged, enriching an increasingly diverse Irish cultural landscape. Somehow however, all of this recedes the gaze of Irish theatre as it continues to imagine an Ireland in which voices from Poland largely do not exist and have no right to tell their own stories.

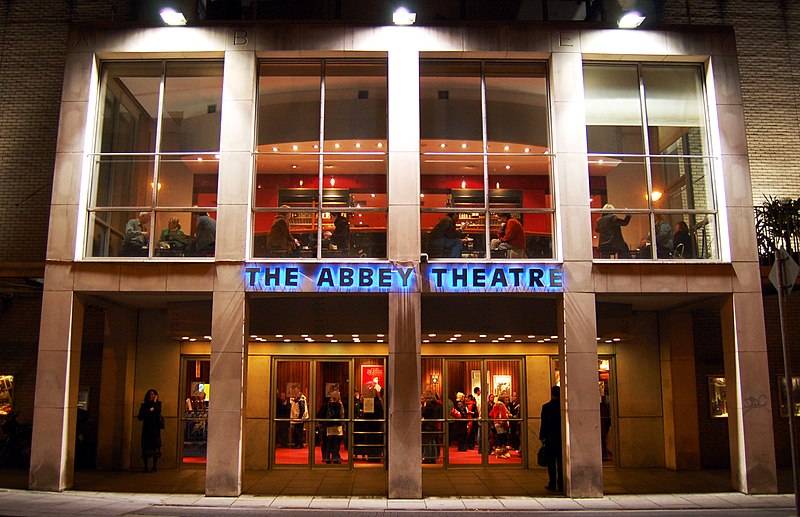

The previous statement takes a bird’s-eye view of Irish theatre and reflects the reality of mainstream theatre more than its fringe. Nevertheless, it is true that apart from some very specific one-off projects, the Irish theatre system has done little to engage with Polish people, their stories, and their creative imaginations. The Abbey Theatre makes a particular example as an institution that historically, symbolically, and financially (as the state-subsidized theatre) has responsibility to perform Ireland. As Ireland’s national theatre it asks, as per its own statement on the website, “who we were, and who are we now?” and what “it is to belong, what it is to be excluded and to exclude” in contemporary Ireland. Yet, for the last two decades, the Abbey has consistently ignored Poles in Ireland.

Even in the rare cases when Polish characters appeared in the Abbey’s productions, Polish perspectives were either absent or marginalized. In Quietly (2012) by Owen McCafferty, the Polish barman (played by Polish actor Robert Zawadzki) had no story of his own, and the only reason for his theatrical existence was to be a sign of contemporary time to situate the moment in which the two Irish characters were revisiting The Troubles. In Shibboleth (2015) by Stacey Gregg – again set in Northern Ireland – there were two Polish characters: Yuri (which is not a Polish name) and his daughter Agnieszka. While Polish Piotr Baumann took the male part, the female part was given to an Irish actor. No Polish actor was invited to audition. This is even though the play had two scenes between Yuri and Agnieszka written to be in Polish. In 2015, I asked the Abbey Casting Director about it. She explained that it was important for the character to have an “authentic” Belfast accent as Agnieszka was raised in Northern Ireland, and while the casted actor did not speak Polish, she would “try her best.” This answer spoke volumes about whose experience as the audience the Abbey valued, and, in turn, who the Abbey saw as the part of Ireland and its audiences. In Rosaleen McDonagh’s Walls and Windows (2021), an Irish actor played a Polish woman Aga. There were no Polish creatives credited in any of these productions, and Polish stories and Polish people were imagined through Irish gaze.

It is also clear that the Abbey particularly ignores the female Polish migrant voices, which links this marginalization to broader discussions on women in the Abbey and Irish theatre. And the problem continues in the Abbey’s upcoming production of Ironbound by Martyna Majok, which will premiere during the 2023 Dublin Theatre Festival. The Polish-born and US-raised Pulitzer-winning playwright wrote the play inspired by her mother’s story and the invisibility of her experience as a Polish migrant. As Majok said in an interview with The Dramatist in 2016:

When she saw it opening night at Round House, she witnessed 300 people in a huge theatre stand up for a story that she knew in her heart is hers. That meant more to me than anything in my career that, that night, she felt seen and valued.

Ironbound is a play written by a woman who grew up in a country in which she was not born and watched her mother being constantly made worthless and invisible. It is a rare instance when Majok explicitly names the character’s nationality. As the action of the play is set across 20 years, the story resonates strongly with today’s Ireland, in which so many Polish young adults grew up watching their mothers being marginalized and othered. To not see that parallel is ignorant of Polish experiences in Ireland for the last two decades. In many ways, it was the perfect opportunity for the Abbey to acknowledge its past failures towards Polish community and announce a change. Yet again, there are no Polish creatives involved and a Polish woman will be performed by an actor from another country in the East of Europe, echoing the stereotype of “Eastern Europeans” as a homogeneous group.

In June 2023, Migrant rights activist Teresa Buczkowska was quoted by the Irish Times saying that “nobody really pays attention to the integration needs of Polish people in Ireland because they are [predominately] white and European.” The Irish theatre system, and the Abbey specifically, has played an important part in this not-paying-attention. By ignoring perspectives, stories, and creative ability of Poles, the Abbey has repeatedly made a statement that it does not value them. This, in turn, suggests that Polish people, according to the Abbey, have nothing to offer to theatre and culture of Ireland. It is of course too late to change the casting of Ironbound. But there is still time for the Abbey to acknowledge its failures towards Polish community and make commitments to make this better. A public discussion would be a start. A more meaningful gesture, however, would be paid internship system to immediately feed Polish migrant voices into the production. Later, this could be developed into a full programme of integrating migrants into the Abbey and Irish theatre on every level as casting directors, actors, composers, directors, artistic directors, and so on. This way the Abbey can lead new imagining of Ireland in which migrants are integral elements of the social fabric.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kasia Lech.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.