Three years before the Xiqu Centre opened as Hong Kong’s first purpose-built center for Chinese opera, award-winning Cantonese opera singer Keith Lai was given a daunting task: choose one opera for the center’s Experimental Cantonese Opera series that could represent the traditional art form. In China, the different vernacular cultures have given birth to over three hundred sub-genres of Chinese opera. Cantonese opera alone can be traced back to the pre-Qin period (2100 BC-221 BC), accumulating thousands of years of folk and stage songs. But Lai didn’t need long to decide. He saw a clear choice right from the beginning: Farewell My Concubine (霸王别姬).

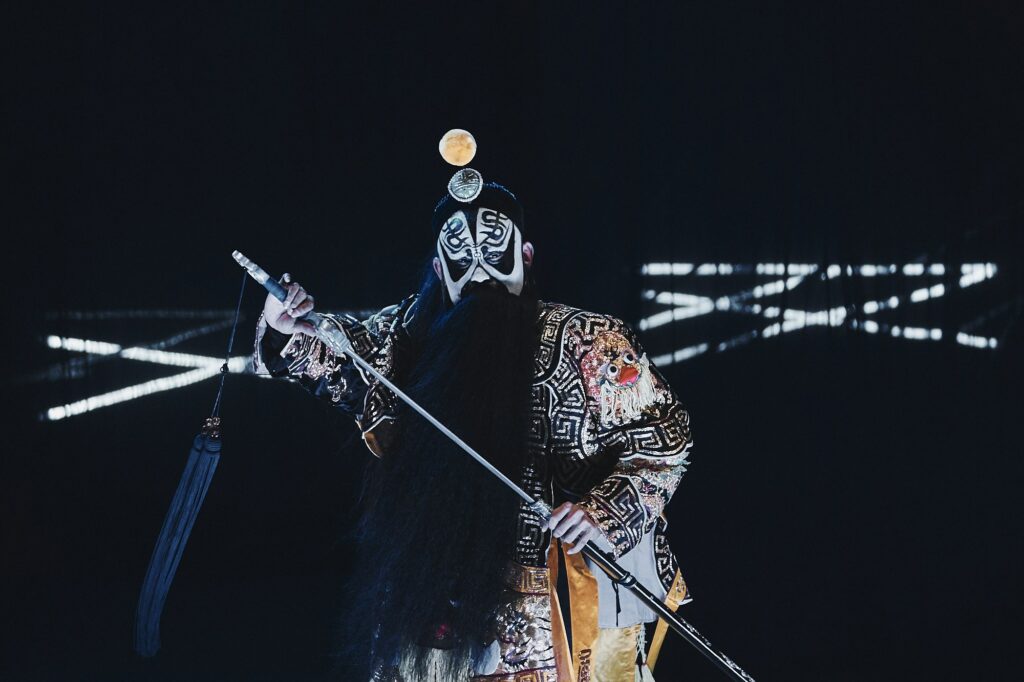

Xiang Yu, played by Keith Lai. Image courtesy West Kowloon Cultural District Authority.

“Farewell My Concubine is a classic among classics,” says Lai, taking a break during a rehearsal at the Xiqu Centre, which opened last November. In 2016, the young performer and his troupe presented his radically revised version of the opera at the Shanghai Centre of Chinese Operas, which had secured a collaboration contract with the Xiqu Centre, still under construction at the time. “We wanted to introduce the past, present and future elements of Cantonese opera to the Shanghai audience,” Lai recalls. “But since they weren’t familiar with Cantonese opera, picking a story that all Chinese knew would enhance their appreciation of an unfamiliar art form.”

It’s an interesting choice because Farewell My Concubine is most commonly associated with Peking opera, not Cantonese opera. It tells the legend of Xiang Yu, the Hegemon-King of Western Chu during the Chu–Han Contention (206-202 BC), who was on the verge of total defeat by Liu Bang, a former brother at arms who ultimately betrayed Xiang in order to take the throne for himself. When Xiang found himself surrounded, he begged his favorite concubine to leave. She refused and danced for him one last time before committing suicide with his sword.

When the opera was first performed in Beijing in 1918, it stunned the audience with its unconventional incorporation of tai chi and tai chi swords. The delicate, flowing movements of the martial art, which is practiced for defense and strength, complements with the soft, flexible blade. Together, they bring out Yu’s passion and elegance in her dance, while the soulful lyrics and strong beats of Kunqu melodies—borrowed from one of the oldest forms of Chinese opera—capture the pain and helplessness of the fallen king.

The opera proved so popular that it has been adapted into other operatic forms, including Cantonese opera, as well as entirely different media: Hong Kong author Lillian Lee penned a novel under the same name, while Chinese director Chen Kaige’s 1993 film based on the novel won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

Lai’s rendition is yet another adaptation but by no means a conventional one. Since its premiere in Shanghai in 2016, it has been re-staged in Black Box Theatre in Hong Kong in 2017 and finally, according to Lai, it “returned home” when the Xiqu Centre opened this past winter. Lai hoped his commission would embody the younger generation’s vision of Cantonese opera by using new technology to enhance the stage effects of traditional theatre, and by exploring the psychological portrayal of characters instead of plainly telling stories through lyrics, as is done in traditional Chinese operas.

But adapting a classic Peking opera into a modern Cantonese opera is no easy feat. “Peking opera is very elaborate in its narrative and character development whereas experimental Cantonese opera is short,” explains Lai. “We can only select the representative parts and the three most significant characters to be included in our production.” He picked Xiang, Consort Yu—the titular concubine—and Xiang’s loyal general, a symbol of Xiang’s 8,000 followers, as the backbone of an abridged story.

In the traditional Peking opera, which emphasizes a story’s narrative, Xiang’s lyrics describe in detail the death of his concubine and general, and his lamentation about the pointlessness of life after their departures. “In contrast, one of the most distinctive features of Cantonese opera is its rich emotions,” says Lai. “In depicting a character’s anger in the iconic sword fight, Cantonese opera singers belt the songs out. In portraying a scene, gongs and drums are used to create rowdiness. Even in our modern version, we want to focus on the characters’ psyche instead of just storytelling.”

Xiang Yu hallucinating. Image courtesy West Kowloon Cultural District Authority.

To achieve this, Lai readjusted the lighting in the opera’s last scene, known as “Suicide at Wujiang River,” to insinuate that the action isn’t taking place in a physical space but instead in Xiang’s imagination, as the heartbroken and delirious king believes he’s encountering the ghosts of his concubine and his general. The ghosts from two sides of the stage are persuading Xiang, who is about to take his own life, to live on and fight another day in order to avenge his lover and friend, despite insurmountable odds. “But are they actually there? Or is it only Xiang’s internal battle?” asks Lai.

But that’s not the only challenge in adapting the opera. How can Lai deliver a compelling production when the legend has been performed so many times in a traditional way? To freshen things up, he rearranged some of the musical compositions. In the battle scene, for instance, percussion and Western string music are arranged on two sides of the stage to heighten the sense of antagonism between Xiang and Liu’s army, when in the traditional staging of Farewell My Concubine, the stage arrangement of Cantonese opera music isn’t as nuanced.

Despite these changes, Lai insists that giving Cantonese opera a contemporary twist isn’t just changing things for the sake of being new. “Cantonese opera music per se is very rich,” he says. If you “blindly” mix it with Western styles of music, “the outcome can be inharmonious and odd.” Instead, he tries to enhance the existing qualities of the traditional art. Janet Wong, who plays Consort Yu, has written new scores for this production, but they all follow the traditional musical format of Cantonese opera. “The new rhythms aptly capture Xiang’s despair when he has nowhere to turn anymore,” he says.

Xiang Yu with a modern stage set design. Image courtesy West Kowloon Cultural District Authority.

Lai hopes his take on Farewell My Concubine will stir new interest in Cantonese opera, which was the main form of entertainment in Hong Kong in the 1950s and 60s. “Back then, Cantonese opera singers were considered as stars,” says Lai. “There were four-hour shows around town every night. One production could last for a few months.”

After TVB made its first television broadcast in 1967, however, free-to-air television programs became Hongkongers’ main source of popular entertainment, the allure of Cantonese opera began to fade. Western opera and Cantopop have further edged it off the scene. Today, Cantonese opera troupes strive to expand their audience by putting on multiple shows in various theatres every few weeks, hoping—sometimes in vain—that they will fit the tastes and preferences of different parts of Hong Kong. That has put a strain on opera casts, who have less time to refine their singing skills when they are performing so often. And the abundance of opera shows hides the fact that audiences have dwindled – they are less numerous and much greyer than before.

Things may be changing with the opening of the Xiqu Centre. Lai has noted that, over the past several months, there has been an increasing number of young people attending contemporary Cantonese operas, which give them a form of entertainment that is at once familiar and fresh. “These young audience members have heard about Cantonese operas from their grandparents and parents but have never seen it,” he says. They may be curious, but they are intimidated by traditional performances that can last for hours. “Our experimental Cantonese opera has been trimmed down to just around an hour-long, and they’re happy to give it a go.”

Has that succeeded in winning over new and old audiences alike? So far, audiences seem to have reacted well to Lai’s experimental production; Wu Tong, deputy director of the Chinese Theatre Literature Association in Beijing, described it as “creative, inspired and intimate.” Lai hopes this can inspire audiences to look at Cantonese opera in a new way. “Sometimes beginners are attracted more by the elaborate and exquisite Peking opera,” he says, “but Cantonese opera, which prima facie can be raw and coarse, is equally worth exploring. I still spend time to talk with retiring Cantonese opera masters, so that our traditional art can be passed down to my and future generations.”

And on that note, a Xiqu Centre worker arrives to fetch Lai; it’s time to head back to rehearsal. He opens the door and returns to the stage, stepping into a brave new world of Cantonese opera in Hong Kong.

This article was written by Zabrina Lo for Zolima CityMag on February 5, 2019, and has been reposted with permission

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.