The growing levels of migration results in an increasing number of children across Europe growing up in multilingual families (Armon-Lotem and Jong de 1), in which they may or may not share languages with their parents, guardians, or extended families. This does not only apply to children from migrant and postmigrant contexts, but also Deaf and/or Blind children growing up in hearing and/or seeing families and hearing and/or seeing children in Deaf and/or Blind families. International experts in child development urged professionals across disciplines to join forces in establishing new systems of support for multilingual families and children. These children’s development varies from those raised in monolingual households. The call emphasized the necessity of questioning educational, developmental, and health services that still regard one-language-speaking children, whose language aligns perfectly with their familial, national, and ethnic contexts, as the norm. This is no longer a norm (Bak et al.). Theatre has an important role to play here.

Even though Europe is multilingual, and its histories and contemporary realities are rooted in multiple languages, European national theatre systems are predominantly national-language-specific, organized by and narrated in (including their history) national tongues (Lech, Multilingual 3). With that comes imagining of the audiences as predominantly native-speakers of the official language(s) (Lech, Multilingual; Lech, “Polish People”). In turn, children raised in multilingual contexts have little opportunities to see these realities reflected on stage and encounter the languages they speak – and that are not the national-languages in the country they reside (so their home) – and their associated cultures on the stage. In turn, children and young people from multilingual contexts face an indirect yet prejudicial statement made by theatres against them: in their home (the country where they grow up), some of their languages, and some of their cultures are less valuable, and, in the cases of migrant languages, have no cultural or public value for at all.

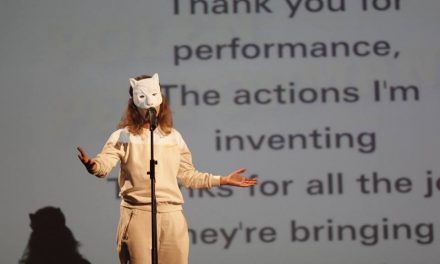

The task to make multilingual theatre for young audiences is an urgent one also because it is underpinned by fundamental human rights: right to performance, language rights, and children rights to participation in cultural and artistic activities and having co-agency in the decision-making process concerning these activities (United Nations; Child Rights Connect). The recently completed Jeune Théâtre Européen Jeunes Publics project (JTEJP), funded by Creative Europe – European Cooperation Projects, shows that using multiple languages in theatre process and performance aimed at young people opens new ways of thinking about audiences, their engagement, inclusion, and social relevance of the performing arts sector.

This experimental initiative ran for two years (between 2022-2023) aimed at creating and performing multilingual shows for children, youth, and families. It involved up-and-coming theatre artists collaborating with experienced mentors, as well as producers and organizers from diverse professional backgrounds and languages. More than 15 languages were involved at different stage: Serbian, Hungarian, French, Finnish, Polish, English, Irish, Arabic, Greek, Amazigh, Tunisian, Albanian, Ukrainian, Russian, German, Arvanitika, and Italian. Additionally, the project engaged amateur performers and young audience members throughout the project’s development stages. The project had seven main participants: l’Espace des Arts, Scène nationale Chalon-sur-Saône (France), ArtFraction (Serbia), Art Veda (Tunisia), Jeune Théâtre National (France), University of Galway (Ireland), Pedio Texnis (Greece), Staastheater Mainz (Germany). It also included five Associated Partners: Compagnie l’Instant même (France), Pistë (France-Finland), Milos International Festival (Greece), Galway Theatre Festival (Ireland), and Branar Drámaíochta teo (Ireland). All these partners ranged from small, grassroots organizations to larger, government-funded entities with significant operational capabilities.

Engaging young spectators with multilingual theatre

The JTEJP approached the task of searching for methods to create theatre in multiple languages aimed at young people in multiple ways trying to create multilingual works and find multilingual modes of working in international contexts and remain in dialogue with various perspectives. One of the approaches was development of multilingual productions and presenting them as work-in-progress to the invited young spectators. Another were multilingual theatre workshops for young participants. Four work-in-progress were developed. Mary’s Monster – led by ArtFraction – centred around a journey of Frankenstein across Europe and its languages. Branar Drámaíochta teo’s Savage was rooted in the legend about Children’s of Lir, and Arabic and Serbian stories helped to highlight the possibility of retelling the national myth from different perspectives. In Art Veda’s Dihya the focus was on deconstructing simplistic narratives on Tunisian history and culture by bringing to light the rich story of Amazigh language and contextualizing it within broader North-African and Mediterranean regions. Pedio Texnis’s Borderline explored racist violence experienced by different communities in Greece and underpinned by power relations between Greek, Albanian, and French languages.

At all work-in-progress showings in Chalon-sur-Saône (France), Tunis (Tunisia), Galway (Ireland), and Athens (Greece), young people (from 8-year-olds to young adults) were invited to workshops with artists, and to comment on the work-in-progress showings. In Ireland, Tunisia, and Greece, the audience matched what the artists imagined as their spectators and came from the same cultural contexts as the leading artists. In Serbian piece (rehearsed in France), the audience were the young adults and theatre-makers in training (age 16-18) from France, and thus came from a different cultural context than the creators of the work. However, regardless of these variables, in all focus groups after the showings, spectators narrated their experiences of these presentations in a strong connection to the artists on stage, whether this was the vulnerability of the artists in the process or seeing the artists as an extension of their community.

For some spectators multilingualism confirmed and validated the importance of traditional languages in their local reality. This was the case of the Ireland’s piece that for the spectators stressed the cultural value of Irish and stretched beyond the context of the island. It would have been interesting to see what would have happened if new languages of Ireland (such as Polish with the biggest non-Irish community) were added. In Tunis, the spectators and their families stressed that multilingualism of the piece reflects communities in Tunis, and they included here disability-led languages.

In Greece, a group of teenage spectators (many with migrant backgrounds) also spoke about the multiple languages speaking to their realities and how their generation saw Greece. This was interestingly contrasted also in the post-show discussion with artists of migrant backgrounds from Greece who narrated racial violence and marginalization in the piece from their perspective. These tensions emphasize hyper-contextual aspects of multilingual works and how they open themselves to various audiences. At the same time, it once again brought to the fore a multiplicity of experiences existing within one national context, and, the discussion surprised the Greek artists themselves, suggesting further exciting avenues to explore in the piece. The spectators of the Serbian piece narrated their engagement through their perceived commonalities of the profession. As young artists in training, they commented on the piece from the perspective of fellow creators, emphasizing how multilingualism speaks to their experiences of the world and also their professional opportunities.

The focus groups on the spectators’ feedback were multilingual acts of searching for more equal encounters in theatre. In Ireland, the discussion with 8–10-year-old spectators and their families was facilitated bilingually in Irish and English by Marianne Ní Chinnéide. In Tunis, the focus group was underpinned by communal translations. I spoke to the families in English (with some help of Polish) and Anne Bérélowitch translated it to French. Some audiences needed further translation to Arabic, language in neither I nor Bérélowitch spoke. My discussions with teenagers in Greece were in English, with occasional Greek words included. In France, young spectators could choose English or French and Bérélowitch acted as a translator. These focus groups included translations, mixing different languages and their rules (codeswitching), and negotiating senses between languages through gestures, tone of voice, and lexical similarities across languages (translanguaging). In doing so, together with young participants as co-agents, we imagined and rehearsed new, more equal, collaborative ways of communicating in theatre.

Multilingual workshops

This also links with how the workshops for young audiences opened participants to thinking about their languages in a new way. In Tunis, after bilingual Greek-French workshops by Pedio Texnis for local teenagers, participants reflected that it helped them to think about communicating in a new way. In Chalon-sur-Saône, Anne Bérélowitch’s and Parelle Gervasoni facilitated a series of multilingual workshops with young actors in training. I observed these, and I also ran the focus group afterwards with the participants. The young actors confirmed their sense of developing general acting skills, especially the sense of increased authenticity, linking them clearly to multilingual contexts. Some said that the session helped them to understand how their life experiences related to languages and mobility can make them better actors. They also confirmed their growing awareness of and confidence in using their linguistic resources after the session, and all clearly related it to their increased employability. For some, it was connected to an increased ability to work internationally, and some expressed that they plan to continue to use multilingualism in how they work as directors, actors, and community artists. All this is in agreement with what I observed in the session.

The professional social benefits grow beyond the timeframe of the workshops. Participants from migrant communities commented on how much it meant for their confidence and sense of self to experience languages they shared with their families as valid means of artistic communication. This opens a question: who could become audiences in theatres if theatres reflected the diversity of local residents, their languages, and noticed creative possibilities that arise from such engagement, if they engaged with artists from these disenfranchised communities?

The JTEJP shows how multilingual theatre for young audiences creates spaces for young people from diverse backgrounds to see that in their home (the country where they grow up), all of their languages and cultures are culturally and socio-politically important and celebrated. It is a politically urgent task underpinned by fundamental human and children’s rights that will create more access points to theatrical realms and society at large, allowing diverse individuals and communities to act as co-creators of these realms.

Read more about multilingual theatre in Multilingual Dramaturgies: Towards New European Theatre.

Works cited

Armon-Lotem, Sharon, and Jan Jong de. “Introduction.” Assessing Multilingual Children: Disentangling Bilingualism from Language Impairment, edited by Sharon Armon-Lotem et al., Multilingual Matters, 2015, pp. 1–22.

Bak, Thomas, et al. Apel Do Specjalistów Praktyków: Dwujęzyczność Jest Normą. 2021, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30268.56961.

Child Rights Connect. Child Participation – Child Rights Connect. https://childrightsconnect.org/children-participation/. Accessed 25 Feb. 2024.

Lech, Kasia. Multilingual Dramaturgies: Towards New European Theatre. Palgrave, 2024.

—. “Polish People Deserve Better from Irish Theatre.” TheTheatreTimes.Com, 7 Sept. 2023.

United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989.

The Jeune Théâtre Européen Jeunes Publics (Young European Theatre for Young Audiences) (JTEJP) project was funded by Creative Europe – European Cooperation Projects.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kasia Lech.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.