Silence. From the Latin “silentium”.

The RAE (The Royal Spanish Academy) defines it as abstention, the lack or omission of something.

Life is full of silence no matter how much we think that there are increasingly more sounds and noises, echoes. We might think our world is overloaded and excessively ornamented. Nevertheless, the silence is more overwhelming than an outcry. Why? Because silence is also to stop acting when one should have acted. A lack of courage. A lack of decision. To look the other way, that too, of course, is silence. And it is devastating.

On February 22, the play La armonía del silencio (The Harmony of Silence) by the author from Alicante, Lola Blasco, was presented at the Teatro Español in Madrid. In the house, a great number of people waited, ready to enter an imaginary world that would only spend two days on stage (much too little time in my opinion, provided by this season’s programmers of Teatro Español).

The work takes us through the story of a Spanish family on a trip of temporary jumps where two children try to recover their grandmother’s piano that, due to ups and downs, had to be sold during the Civil War. The plot lines are interspersed in temporal ellipses that go from the years of prewar and Civil War to the recent 2016. We are put before one of those stories, a puzzle to be solved in the process. The result is very interesting, for it is dealt with in a way that is not linear. At the end of the day, you just have to read that disordered story that Blasco writes: a way of telling that looks like life itself. The fable—because yes, this is a fable open to interpretation—covers the idea of symmetry and the order of things, although this order operates at surrealist levels.

The idea of fate manifests in the serendipities that occur in the story: note, for example the narration around the rhythm and harmony of the celestial spheres (at this time, NASA has revealed that they have found seven planets orbiting around a red dwarf) and the music of the universe—because music is very present in the text and subtext of Blasco’s piece.

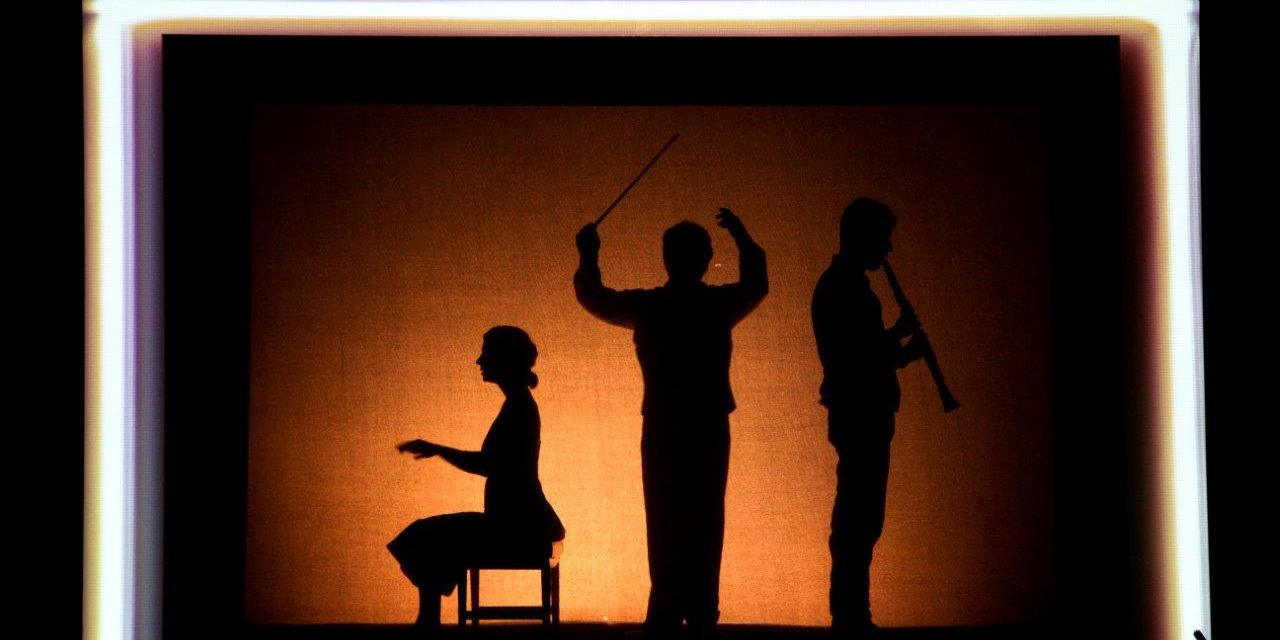

A scene in La armonía del silencio. Photo courtesy of Teatro Español.

There is a disordered order in this work, a structure that has a lot of drama and playfulness. A disordered order that you only understand at the end, like when someone explains the mechanics of a CAT scan and tells you about the proton shock, but you cannot understand until your body is scanned in an image on a screen.

Here, the body that is revealed to us is a mutilated, aching body, riddled with evil. EVIL—like this, in capital letters—that becomes worse, the more silent, the more harmonious. There is harmony in evil and Blasco exposes us —in a didactic way—in one of the scenes of the work in which the photos of the reprisal victims during the Civil War seem so similar and keep so much “harmony,” so many resonances, with those of the Syrian or Afghan refugees left to their fate in this silent Europe.

Highlights of the production are Luis Perdiguero’s very accomplished choreography with a mesmerizing ability to evoke the imaginary and the video-projections by Álvaro Luna, that foregrounds the documentary character of the work.

A scene in La armonía del silencio. Photo courtesy of Teatro Español.

As for acting, the versatile and exultant Luis Bermejo executes soliloquies or dialogues in an absolutely natural way, demonstrating his chameleon skin when he acts as a ferocious wolf or when his role takes him to grotesque comedy without falling into stupidity. He is believable and his presence the most remarkable element of the production, in my view. In fact, he embodies a character corrupted by the silence of a dogmatic and castrating upbringing. A left-handed upbringing, hard and with no silk glove: the semblance of a man who believes that women are errors in the equation and that only men can understand and inhabit the outdoors. It remains in my memory, that wonderful metaphor that Lola Blasco offers us about social classes and instruments within an orchestra. Perhaps it can be inferred that a criticism is being made — and made by a woman—about the misogyny still prevailing in our environment and that in 2017 many things still remain to be removed. As if women were a simple flute in an orchestra but still could not be a piano.

Lola Blasco’s style is scholarly. She twists the text concerned with nuances, recesses, explanation and documentation, and, of course, full of symbols. Perhaps that scholarship and an excess of didacticism can make one lose attention on the fable at some moments. Because, yes, this is a tale, and in this story there are dungeons, “Rómulas” and “Remas” weaned claiming poetic justice. There are victors and losers, a Spain that was often silenced. Yes. In this story there are ferocious wolves and she-wolves forced to mend pants, there is the memory—historical memory—and a moral in the threat of what silence or forgetfulness can suppose. There is a reflection on the generational situation transferred in an accurate way to the two grandchildren, who in 2016 are torn between ignoring or counting the damages. There is a Little Red Riding Hood who has stopped caring about the vermin that may assail her, because she has found the way or the way has found her and she does not think to deviate for a single inch. There is music, there are people who look at the planets and understand that music but are not able to look within themselves. There is a phoenix embroidered in a jacket that is nothing but an emblem embroidered on a final note of this whole score that sounds, resounds and says: it is one thing to be silenced, it is another thing to be silent.

La armonía del silencio

Text and direction: Lola Blasco.

Cast: Luis Bermejo, Antonio Lafuente, Ana Mayo, Mélida Molina and David Tenreiro.

Lighting and Set Design: Luis Perdiguero (AAI).

Projections: Álvaro Luna.

Costumes: Joan Miquel Reig / Fondos CulturArts Teatro y Danza.

Musical Composition: Vidal.

Scenic Construction: Orange Ocean.

Assistant Director: Irene Coloma.

Lighting and Set Design Assistant: Vanesa Hernández.

Projections Assistant: Elvira Ruiz Zurita.

Production and Distribution: Carlota Guivernau.

Production: Institut Valenciá de Cultura.

This article was originally published in Spanish in the author’s blog Mi reino por un caballo here. Reposted with permission. @EfeJotaSuarez

Translation: Yasmin Zacaria Mikhaiel.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by EfeJota Suárez.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.